Working People Need Access to Paid Leave

By Emily Andrews, Sapna Mehta, and Jessica Milli

Executive Summary

Bonding with a new child, recovering from a serious illness or injury, or caring for a sick partner or an aging parent—these are some of life’s most important moments. Almost everyone will experience a caregiving need at some point in their lives. But despite the universal need for care, the United States does not guarantee working people any paid time away from work, and many employees aren’t even entitled to unpaid leave.

In the absence of a federal policy, 13 states and Washington, D.C. have established state paid family and medical leave programs. Under these programs, working people can take time to welcome a new child, care for an ill loved one, or recover from their own serious medical illness or injury while receiving some pay. Workers can also use many of these programs to address needs related to military deployment or domestic or sexual violence.

Utilizing data from the Worker Paid Leave Usage Simulation Model (Worker PLUS), we estimate the current need for leave in those states that do not have established paid family and medical leave programs; the extent to which the need for leave goes unmet in these states; and the economic losses that families incur as a result of unpaid or partially paid leaves. This report presents our overall findings in these states; we also provide state-level estimates in the Appendix. While workers face an unmet need for leave even in states with paid family and medical leave programs due to work requirements, employer carve-outs, and other barriers to leave-taking, this report focuses exclusively on where the largest unmet need for leave exists: in the 37 states that have not passed paid family and medical leave policies.

Our analysis finds that in these 37 states:

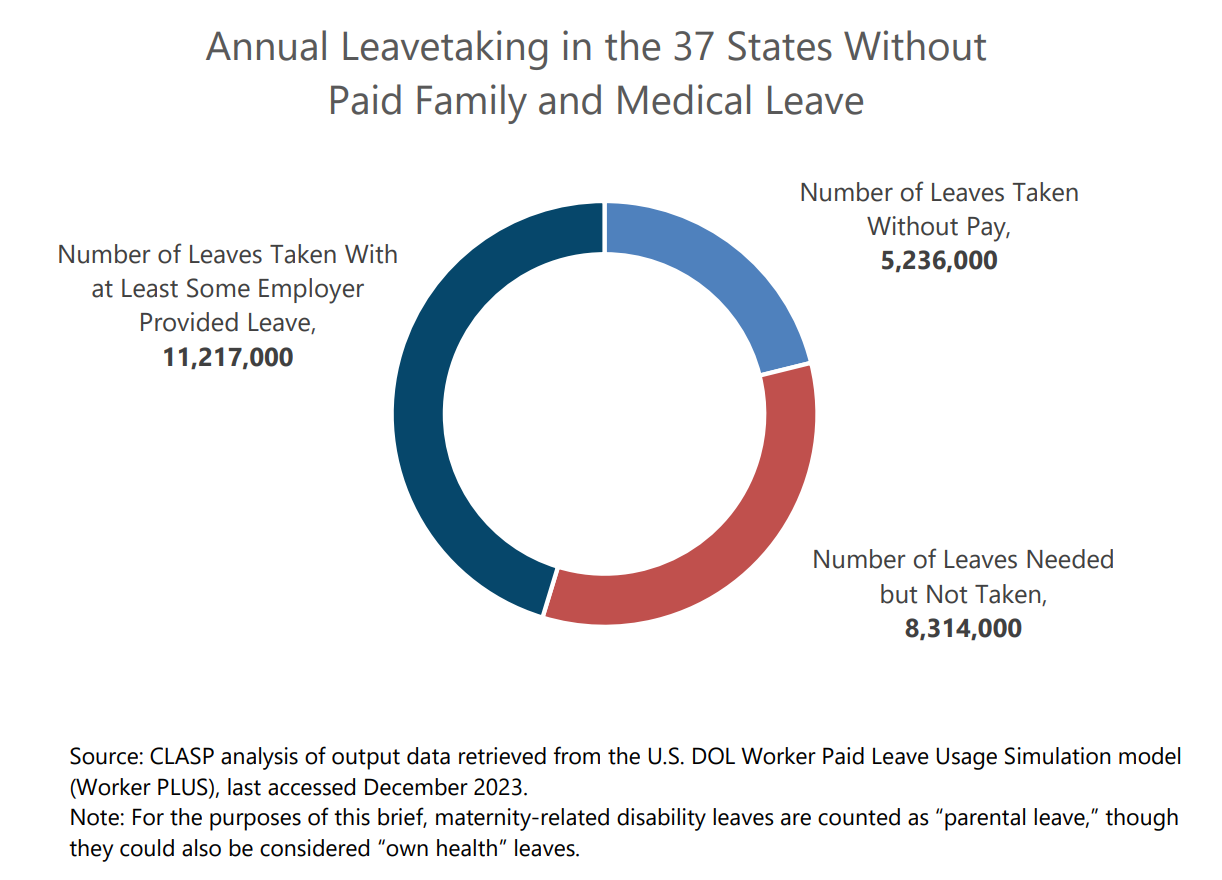

- Nearly 16.5 million leaves are taken each year, with 5.2 million, or 32 percent, taken without pay, resulting in billions of dollars in lost wages and increased economic insecurity and hardship.

- Over 8 million leaves are needed but not taken each year, including leave to care for a new child or a sick loved one, or to recover from a serious medical condition.

- Over 54 percent of the leaves needed each year are either not taken or taken without pay, forcing workers to choose between a paycheck and their own health or the health of their families.

- Workers and their families in these states lose an estimated $34 billion in wages annually

due to unpaid or partially paid leave. - Women are more likely than men to take leave that is either unpaid or only partially paid, causing women to lose nearly $19 billion each year —$3.2 billion more than men lose on an annual basis, even though men make up a larger percentage of the labor force and there is a sizeable and persistent gender pay gap.

Without Paid Family and Medical Leave, Workers Go Without or Lose Pay on More than Half of Needed Leaves.

Our analysis also finds that women of color are disproportionately impacted by the lack of paid family and medical leave. In states without paid leave programs, Native American women, Black women, and Latinas are more likely than white women not to take needed leave, and Black women who take leave are more likely than white women to take it unpaid. Due to occupational segregation and racism in the labor market, on average women of color earn less than their white counterparts and are less able to take leave that may jeopardize their family’s economic security. Similarly, they are more likely to return to work early because they cannot afford extended periods without income.

Geography and regional demographics play important roles in the lack of paid leave for women of color. Forty-two percent of women of color reside in the South, where–with the exception of Maryland, where Democrats have controlled the state legislature for decades–not a single state has passed paid family and medical leave. Given the political makeup of this region, it is unlikely that any additional Southern state will pass a paid family and medical leave program, making federal action on this issue all the more urgent due to the gender and racial disparities in the region.

The scope of unmet leave extends beyond the workplace, as not taking needed leave can lead to compounding health and financial costs. Research suggests that paid leave supports improved health outcomes, including improved infant and toddler development, better maternal mental and physical health, increased breastfeeding rates, reduced infant mortality, and increased ability to afford and complete cancer treatments. Paid leave also supports household economic security following the birth of a child and makes it more likely that individuals with serious health conditions, like cancer, can remain in the workforce.

In addition, paid leave supports greater labor force participation, particularly among women. The implementation of a paid family and medical leave program has been shown to increase the number of mothers in the workforce the year after the birth of a child by 6 percent, reducing new mothers’ labor market detachment by 20 percent in the first year after giving birth.11 Increased labor force participation results in greater economic activity. According to the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), if women in the U.S. had labor force participation rates similar to women in Germany and Canada, both of which have national paid leave policies, we would generate more than $775 billion in additional economic activity per year. Paid leave also benefits businesses by supporting recruitment efforts, decreasing turnover costs through greater retention, and increasing worker morale and business productivity.

Despite the recent momentum at the state level to pass paid leave laws (see chart on page 6), the majority of working people in this country still lack access to paid family and medical leave. In this brief we utilize data from the DOL Worker Paid Leave Usage Simulation model (Worker PLUS) to estimate the need for paid family and medical leave and wages lost among workers taking unpaid or partially paid leave in the states that do not have paid leave programs.

About the Worker PLUS Model

The Worker PLUS model was developed for the DOL in response to the growing interest at the state and local level to develop and implement paid family and medical leave programs. It addresses the limited availability of data at the state level on workers’ need for leave and leave-taking behaviors by modeling them with the 2018 Family and Medical Leave Act employee survey and simulating them onto each state’s sample in the 2020 5-year American Community Survey (ACS). The Worker PLUS model also enables users to simulate the potential effects of a state program on worker leave-taking compared with current leave-taking and estimate the associated costs of proposed programs.