Why Investing in Child Care Providers is Essential for Providers, Children, and Families

By: Jessica Milli

Written with support from Center for Law and Social Policy, National Women’s Law Center, and The Century Foundation.

Child care is an essential service that parents rely on so they can work, attend school, or participate in training while knowing their children are well cared for in a stable and nurturing environment. For too long, child care has been out of reach for many families due to the lack of available care and the high price. This was exacerbated by the pandemic when child care programs closed—both temporarily and permanently. Compounding these challenges has been that fact that child care workers have been leaving the sector due to persistent low wages and lack of benefits. Public investment in child care is desperately needed in order to support living wages for child care workers and alleviate the current shortage of affordable and reliable child care options for families.

Employment of child care workers has steadily declined since 2011, a trend exacerbated by the pandemic

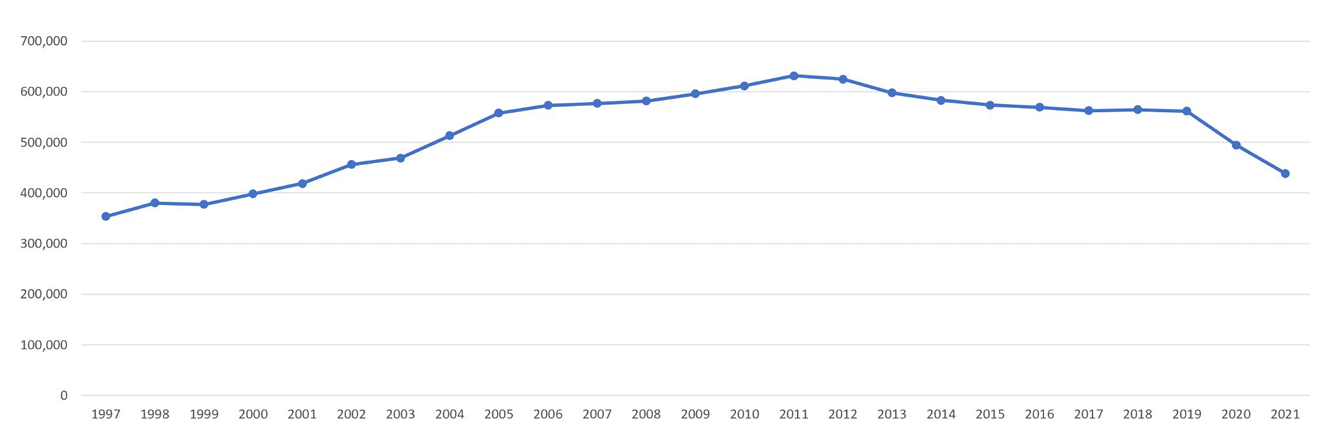

While the late 1990s and 2000s ushered in a significant increase in the employment of child care workers[1] of 79 percent, from about 353,000 in 1997 to 631,000 in 2011, employment peaked in 2011 and has seen a slow decline since then. By 2019, employment had dropped by 11 percent compared with 2011 (Figure 1).

The pandemic only accelerated these trends with the closure of child care programs across the country. Between 2019 and 2020 alone, employment of child care workers decreased by 67,000 (12 percent; Figure 1). And according to recent jobs reports, the child care workforce is still more than 10 percent below its pre-pandemic levels.[2] This is particularly troubling not just because overall employment across sectors is only about 2 percent below its pre-pandemic levels but also because of the huge unmet need for affordable and accessible child care among parents.

Figure 1. Total Employment of Child Care Workers by Year, 1997-2021

Notes: Data are for SOC code 39-9011, Childcare workers. This is defined as workers who “Attend to children at schools, businesses, private households, and childcare institutions. Perform a variety of tasks, such as dressing, feeding, bathing, and overseeing play. Excludes “Preschool Teachers, Except Special Education” (25-2011) and “Teaching Assistants, Preschool, Elementary, Middle, and Secondary School, Except Special Education” (25-9042).” Source: 1997-2021 May Occupational Employment and Wages data series, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Alongside the decline in employment among child care workers is a striking decline in the number of providers accepting children with Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) subsidies. Between FY 2008 and FY 2019, the number of providers accepting children with CCDBG subsidies has declined by 60 percent, with only 244,055 providers accepting children with CCDBG subsidies in FY 2019,[3] though the largest decline has been among family care providers (a decline of 67 percent compared with just 18 percent among center-based providers).[4] The data also show a parallel decline in the average monthly number of children served by CCDBG, though there have been small increases between FY 2018 and FY 2019, indicating both fewer providers participating and fewer families receiving assistance.[5] CCDBG resources were stagnant from year to year prior to FY 2018. This lack of investment made it nearly impossible to reach more children or pay providers more, even as the cost of care continued to increase. Providers who do not serve children receiving subsidies have cited a number of administrative and financial burdens to doing so, including problems with voucher payments (i.e., low rates, delayed payments, or inaccurate payments) and the need to devote significant staff time to managing the voucher system’s administrative requirements.[6] The combination of these two forces has meant that the shortage of child care workers has likely hit families with low incomes the hardest.

Low and stagnant wages drive child care workers out of the sector

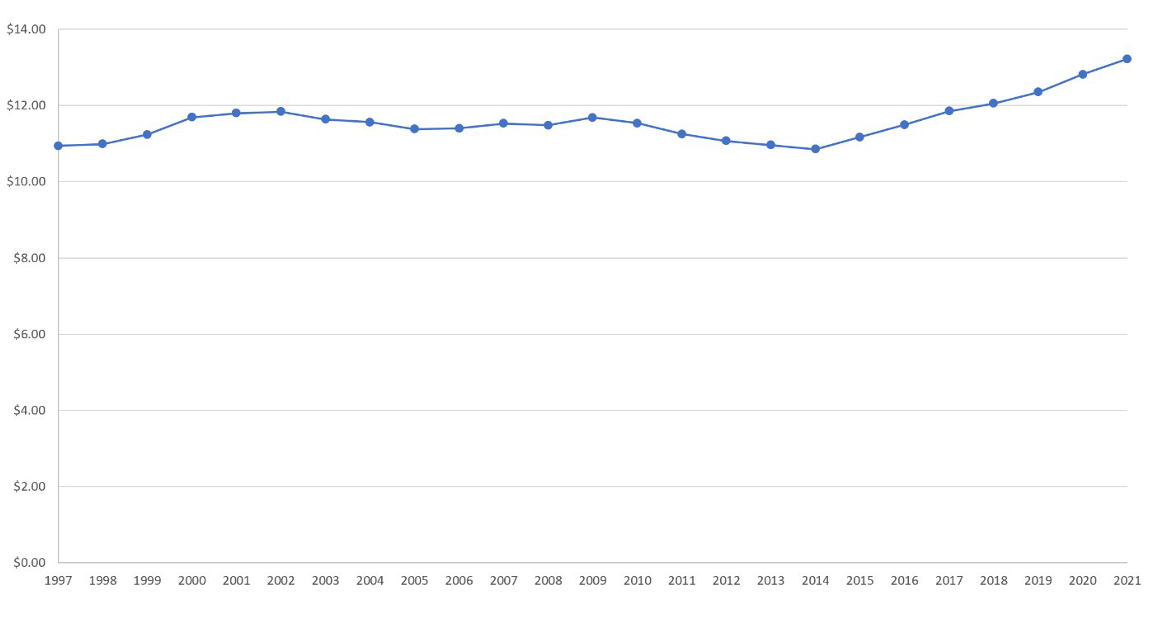

Median real hourly wages among child care workers are low and have barely increased since 1997 (Figure 2). In addition, the current structure of most child care programs provides few opportunities for teaching staff to advance into higher-level and higher-paying roles. These persistent low wages and a lack of advancement opportunities provide little incentive for child care workers to invest in skill development, though many are often required to seek more training regardless of compensation levels. This results in significant disparities in wages between college educated child care workers and workers across sectors,[7] and may be driving some of the decline in employment, as child care workers leave the sector for higher-paying options.[8] It is also important to note that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data presented in this brief do not include self-employed individuals and may leave out a significant share of family child care providers who often have lower earnings and are more financially sensitive to changes in demand.[9] Inclusion of these child care providers in average wage calculations may result in lower wage estimates than those presented here.

Figure 2. Median Real Hourly Wages Among Child Care Workers by Year, 1997-2021 (In 2021 Dollars)

Notes: Data for child care workers are for SOC code 39-9011, Childcare workers. This is defined as workers who “Attend to children at schools, businesses, private households, and childcare institutions. Perform a variety of tasks, such as dressing, feeding, bathing, and overseeing play. Excludes “Preschool Teachers, Except Special Education” (25-2011) and “Teaching Assistants, Preschool, Elementary, Middle, and Secondary School, Except Special Education” (25-9042).” Hourly wages for each year have been adjusted to their 2021 equivalents using the CPI-U for ease of comparison across years. Source: 1997-2021 May Occupational Employment and Wages data series, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Wage levels are not, and have not been, sufficient to meet the needs of child care workers. Poverty rates are substantially higher among child care workers than they are among K-8 teachers, and child care workers consistently have had higher utilization rates of public assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.[10] Further, a child care worker who works full-time year-round (defined by the BLS as 2,080 hours per year) would earn $27,498 a year. According to the BLS, the average single person spent $17,296 on housing in 202011—68 percent of the median full-time year-round earnings of child care workers. Most financial experts recommend that individuals should spend no more than 30 percent of their pre-tax income on housing. In addition, the BLS estimates that the average single person spent approximately $6,871 on transportation expenses, $5,168 on food, and $3,516 on health care in 2020.[12] Adding these expenses to the average annual housing expenditures and adjusting to 2021 dollars totals nearly $34,400 in annual expenses—nearly $7,000 more than the median annual earnings of a child care worker working full-time year-round in 2021.

Child care workers are passionate about the work they do, yet turnover is exceptionally high, with some estimates suggesting that the average annual turnover rate among child care staff can be as high as 30 percent.[13] Low compensation and a lack of benefits are major drivers of turnover among child care workers. One qualitative study, for example, found that child care center teaching staff and center directors were more likely to quit if they earned lower wages and that only half of those who left continued to work in child care.[14] Another study surveying over 10,000 current and former child care workers in North Carolina in 2019 found that 57 percent of workers who were no longer classroom teachers or assistant teachers had left to work in another field entirely. Further, 41 percent of those who were no longer classroom teachers or assistant teachers left those roles because they wanted to earn more money, 25 percent wanted better benefits, and 20 percent wanted better working conditions.[15] Of course, other factors such as inadequate administrative support, job stress, a lack of respect for the work they do, and other personal and environmental factors are also important drivers. For many child care workers, it would seem that passion for the work alone is not enough to surmount the financial difficulties associated with the sector’s low wages.

A lack of benefits and workplace supports, along with stressful working conditions, are also driving child care workers out of the sector

Low wages are only part of the story. Other measures of job quality have historically been low, and some have declined in recent years, which may also be contributing to the decline in employment in the sector. For example, a recent analysis showed that just 20.7 percent of child care workers have access to employer-sponsored health insurance compared with 52.2 percent of workers across all sectors. Moreover, only 10.2 percent of child care workers had a pension or other retirement plan through their employer, whereas 35.0 percent of workers across all sectors did.[16]

In addition, child care is an essential service that requires significant skills to perform. Despite this, there remains a lack of respect for and valuation of the work that child care workers do, rooted in the fact that child care has historically been unpaid labor done primarily by women, beginning centuries ago with enslaved women who provided care for their slaveowners’ children. Child care work is often devalued as “looking after” children, but in reality, it is complex work that involves facilitating both education and skill development in young children at a critical time of foundational brain development, all while providing a nurturing and enriching learning environment.[17] As such, ongoing participation in professional development is important to ensure teachers have the resources, skills, and support needed to effectively manage classrooms and advance in their careers. However, the current professional development system available to child care workers tends to be under-resourced and fragmented. Most states do not have training requirements, and how workers access professional development activities can vary significantly across programs and settings. And while most teachers, regardless of setting, have participated in professional development activities, relatively few have been able to participate in more intensive coaching, mentoring, or college coursework. Further, across most settings, fewer than half of teachers receive support to participate in professional development activities. Moreover, many programs, particularly private programs, require teachers to participate in off-site trainings or courses in the evenings or on the weekends or to take unpaid time off to fulfill their training requirements,[18] and as previously noted, these professional development activities often do not lead to higher compensation in the sector.

Child care can also be a stressful occupation. Low wages themselves can be the source of significant stress among workers and their families. A survey conducted from late 2012 to early 2013 by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, for example, found that 57 percent of teaching staff were somewhat to strongly worried about their family’s economic wellbeing. Worries about having enough money to pay monthly bills, paying for routine health care costs, and retirement savings were among the biggest sources of financial stress.[19] Caregiving work and the work environment itself can also be a source of stress. Lack of support, challenging child behavior, and the responsibility for providing a warm, nurturing, and enriching environment for children to learn and grow can all contribute to stress in the profession. One study found that 35 percent of child care workers somewhat or strongly agreed that they have felt stressed out by the day-to-day demands of caring for children in the past month.[20] Unfortunately, stress can impact workers’ ability to provide quality care for children.[21]

Public investment in the child care sector is necessary in order to raise wages, attract and retain workers, and serve children and families well

The challenge for the child care sector is that it is a labor-intensive service that often operates on very thin profit margins (estimates range from 1 percent to 6.5 percent). This means that in order to raise child care worker wages, providers would need to raise their prices to compensate. Yet the cost of child care is already financially prohibitive for many families. 2020 data from Child Care Aware of America, for example, show that the average annual cost for two children in center-based care is significantly higher than the average annual cost of rent in many states, ranging from 21.5 percent more in Mississippi to 155.8 percent more in Massachusetts. This leaves the child care sector in a triple bind:

- Child care worker wages are low and the industry is losing many qualified workers as a result.

- Because of the sector’s thin profit margins, child care programs are not able to increase wages for workers without increasing the price of a slot.

- Many families cannot afford current prices and would not be able to afford the increases in price needed to raise worker wages sufficiently.

This is why we need public investments in our nation’s child care infrastructure to support living wages for child care workers. Increasing compensation is key to attracting and retaining qualified educators and alleviating the current shortage of affordable and reliable child care options for families. Significant, long-term investments in child care and preschool through the Congressional budget reconciliation process would provide funding so that all families can access affordable child care, so that we can develop high-quality child care infrastructure, and so that workers can be paid higher wages without passing on the cost to families.