Underemployment Just Isn’t Working for U.S. Part-Time Workers

Executive Summary

By Lonnie Golden and Jaeseung Kim

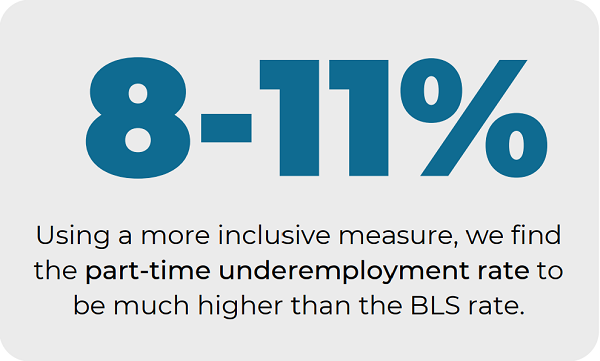

More than 10 years after the Great Recession of 2007-2009, media stories were reporting a healthy, robust economy with lower unemployment and underemployment. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) uses a single indicator of underemployment, those who work part-time (considered fewer than 35 hours per week) but who want and are available to work full-time (35 or more hours). This proportion remained stubbornly high many years into the recovery, peaking at over 6 percent in 2009, dropping only gradually to under 4 percent after 2016. However, this single statistic has masked the breadth, severity, and persistence of underemployment within the US economy. We create a measure of underemployment broader in scope, which includes any part-time worker who prefers more work hours, not just those who want a full-time job, that we are calling the “part-time underemployed.” Using this more inclusive measure, we find the rate of underemployment to be higher—from 8 to 11 percent, in 2016, double the rate of the narrower BLS measure. Thus, about one in every ten workers in the US labor market were underemployed part-time workers. This figure is climbing again in the Spring of 2020, due to the crisis in labor markets spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic. This report provides clues for the likely incidence and harms of more widespread underemployment.

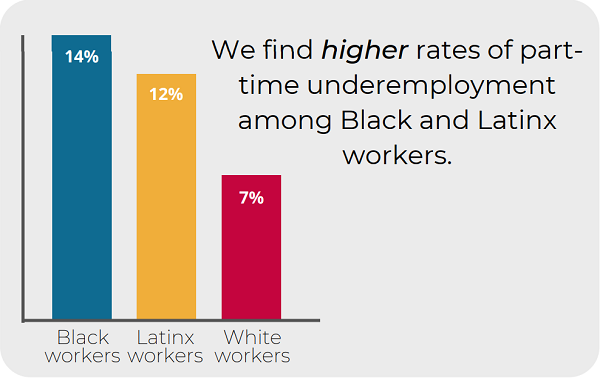

Underemployment disproportionately afflicts people who have been historically marginalized and anybody facing barriers to economic security. Using these broader measures, our study finds that 4 in 10 part-time workers prefer more hours of work, compared to wanting the same or fewer hours. We also find a higher rate of part-time underemployment among the following groups, as a share of total employment:

- Black and Latinx workers. 14 percent of Latinx workers and 12 percent of Black workers, compared to 7 percent of white workers.

- Youngest and oldest workers. 21 percent of workers age 26 and under and 15 percent of those age 65 and over, while underemployment is no less than 6 percent for any one age bracket.

- Women and people who are not married. 11 percent of women, compared to 7 percent for men, 14 percent of non-married workers, compared to 5 percent of those who are married.

- Workers in the lowest third of family incomes. 21 percent for workers in the lowest third of family income, compared to only 4 percent of people in middle/higher income levels.

- Workers paid hourly. 12 percent of hourly paid part-time workers, which is in stark contrast to 2 percent of those paid a salary.

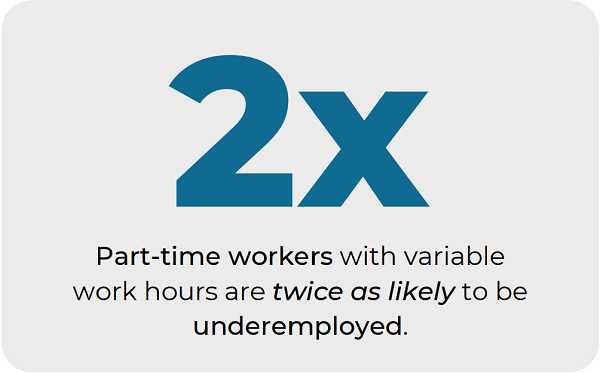

- Workers with variable work schedules. 15 percent of workers with variable schedules vs. 7 percent of those with fixed schedules.

- Workers in certain industries. 15 percent in leisure/other services; 13 percent in education/health services; 12.5 percent in transportation; and, 9 percent in wholesale/retail trade.

- Workers in relatively lower wage occupations. 21 percent in service jobs; 11 percent in transportation/materials moving; and, 10 percent in sales and related jobs.

Part-time workers face barriers to getting more, desired hours—which comes at a high cost to their wellbeing and that of their families and employers.

Underemployment may be particularly pernicious for part-time workers, relative to both people working full time and those who voluntarily choose to work part time. Underemployed, part-time workers experience adverse harmful consequences including:

By implication, underemployed part-time workers experience the hardships and restraints associated with systemic declines in job quality. While this report does not establish the reasons for higher underemployment, we believe these patterns of underemployment may be tied to ongoing structural changes in low-wage labor markets, such as domestic outsourcing, scheduling technologies, or shifting bargaining power and de-unionization. At least partially, these changes are likely driving the pervasiveness and high concentrations of part-time workers’ underemployment in service, transportation and sales occupations and in industries such as retail, hospitality, food service, and other services. These are the fastest growing job sectors. Furthermore, these low-wage job sectors disproportionately employ women and people of color.

This concentration may be due in part to the pervasiveness of systemic racism and ongoing1 racial and sexual discrimination in the labor market. Moreover, most of these relatively lower- wage jobs may tend to have impediments to financial security and work-family balance. Such jobs provide few benefits, offer limited access to paid leave, unstable work hours and schedules, and restrict paths to advancement or career growth.2

Recommendations

In response, we offer a wide range of policy recommendations to curb some of the causes and harms of underemployment. These potential solutions would safeguard and promote the economic security of underemployed part-time workers. Many of these policies are critically needed due to the impending recession sparked by the pandemic, which is further exposing the harms created by inaction and the absence of such policies. These policies should be adopted immediately. Our recommendations:

1. Expand Fair Workweek Laws

State and local governments have passed laws addressing unstable and unpredictable scheduling practices.3 They include provisions ensuring that large employers give employees a minimum advance notice of their schedules and are compensated for late changes to their schedules or for having less than a minimum rest time between shifts;. The federal Schedules That Work Act parallels many of these fair workweek laws.4 Such laws contain other key provisions, including:

-

Access to Hours: Requirements that large employers offer newly available work hours first to qualified, existing part-time workers before hiring new employees, temps, or subcontractors. Should covered employers instead hire new employees, contract, or temp workers first, they would have to compensate the existing employees.5

-

Rights to Request: Provisions that employees have a right to request flexible work arrangements or alterations to their work hours or schedule, without fear of retaliation or discrimination or discharge from their employer.6

- Part-time Parity: Laws that ensure part-time and full-time workers are treated equally on pay rates and the accrual of benefits.7 San Francisco’s Retail Workers Bill of Rights includes part-time parity and the new federal Part-Time Worker Bill of Rights Act would do the same.8

2. Advance Minimum Hours Provisions

Ensure workers get scheduled for a certain minimum number (or “floor”) of hours, such as 24 or 30, to sustain their weekly earnings.9 In the United States, such laws are still scarce, offered only for cleaning or maintenance jobs in large commercial buildings.

3. Increase the Minimum Wage and Strengthen the Equal Pay Act

Increasing the minimum wage to $15 an hour, indexed to inflation, would strengthen the economic security of underemployed workers. Numerous states have modeled this approach in their policies, which the federal Raise the Wage Act also proposes.10 Furthermore, while the Equal Pay Act of 1963 made it illegal for employers to pay unequal wages based on gender, women continue to face a wage gap that threatens their economic security. The federal Paycheck Fairness Act would help end this wage gap by closing loopholes and strengthening provisions of the Equal Pay Act.11

4. Strengthen Collective Bargaining and Co-enforcement Structures to Include Part-time Workers

Employers have many ways to improve part-time job quality in their workplaces. Strengthening and protecting workers’ union rights is critical to increase the quality of virtually all jobs. Letting workers and community groups help implement and enforce local labor standards can ensure these vital protections reach all workers, especially those with less voice and more vulnerable to being exploited—such as workers with low incomes, immigrants, and workers of color.

5. Expand Short-time Compensation (STC) Programs

Overseen by the U.S. Department of Labor, state unemployment insurance (UI) agencies usually administer Short-time Compensation (STC) benefit programs. These programs are designed to avert layoffs in economic downturns. If employers plan to reduce workweeks for employees, in lieu of layoffs, they can apply to use UI funds to subsidize those on work-sharing arrangements. Workers hurt by the reduced time can become eligible for STC benefits to replace a portion of their lost earnings. In the federal response to the economic crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government will fully reimburse states for their existing STC programs.

6. Expand and Update Public Benefits Eligibility without Work Reporting Rules

Pervasive underemployment increases workers’ and families’ need for programs that support basic needs such as cash assistance under Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps), Medicaid, child care assistance, and unemployment insurance. These programs should not include arbitrary work reporting requirements, which deny people assistance when their work hours fall below a certain threshold. Policymakers can provide economic security for more working families by widening eligibility for these programs to include people facing barriers to working more hours.

7. Increase Access to Paid Leave

Twelve states and 23 jurisdictions have passed paid sick day laws to give workers job-protected sick time for short-term illnesses (generally at least five to seven days annually for full-time workers and prorated for part-time workers). Eight states and the District of Columbia have adopted paid family and medical leave laws, which provide paid leave to help workers recover from a serious illness, bond with a new child, or care for a seriously ill loved one. The need for this has been amplified during this COVID-19 health crisis since it would help prevent the spread of contagion while also keeping workers attached to their jobs. Members of Congress have introduced federal legislation—the Healthy Families Act for paid sick days and the FAMILY Act for paid family and medical leave—modeled on these state laws.

The report also suggests further research and data collection that would inform the effort to create more economic mobility for lower-wage workers who want more hours and increased income. These study recommendations could also help create an economy that works for all in the face of the changing nature of work.

The Center for Law and Social Policy will publish the full report in Summer 2020.

Endnotes:

1. Jhacova Williams and Valerie Wilson, “Black workers endure persistent racial disparities in employment outcomes” Economic Policy Institute, August 27, 2019.https://www.epi.org/publication/labor-day-2019-racial-disparities-in-emp… E. Weller, “African- Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good Jobs”. Center for American Progress, December 5, 2019 https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/12/05/47815… jobs/; and D. Pager Western B, Bonikowski B. “Discrimination in a Low-Wage Labor Market: A Field Experiment.” Am Sociol Rev. 2009;74(5):777‐799. doi:10.1177/000312240907400505 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2915472/Nina Banks. “Black Women’s Labor Market History Reveals Deeply Seated Race and Gender Discrimination.” Economic Policy Institute, February 2019. https://www.epi.org/blog/black-womens-labor-market-history-reveals-deep-… Funk and Kim Parker. “Gender Discrimination Comes in Many Forms for Today’s Working Women.” Pew Research Center, December 2017. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/12/14/gender-discrimination-c…

2. Pronita Gupta, Tanya Goldman, and Eduardo Hernandez. “The Struggles of Low-Wage Work.” Center for Law and Social Policy, May 2018. https://www.clasp.org/publications/fact-sheet/struggles-low-wage-work

3. See Julia Wolfe, Janelle Jones, and David Cooper, ‘Fair workweek’ laws help more than 1.8 million workers: Laws promote workplace flexibility and protect against unfair scheduling practices. Economic Policy Institute, Report, July 19, 2018. Also see: https://nwlc- ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fair-Schedules-Factsheet-v2.pdf

4. “Why We Need the Schedules That Work Act.” Center for Law and Social Policy, November 2019. https://www.clasp.org/publications/fact- sheet/why-we-need-schedules-work-act

5. Elizabeth Warren.“Senator Warren & Representative Schakowsky Unveil Legislation to Strengthen Part-Time Workers’ Rights as Holiday Shopping Season Begins.” December 2019.ttps://www.warren.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/senator-warren-and-represe… schakowsky-unveil-legislation-to-strengthen-part-time-workers-rights-as-holiday-shopping-season-begins

6. “State and Local Laws Advancing Fair Work Schedules.” National Women’s Law Center, October 2019. https://nwlc- ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fair-Schedules-Factsheet-v2.pdf

7. Ibid.

8. Elizabeth Warren. “The Part-Time Worker Bill of Rights Act.” December 2019. https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Part- Time%20Worker%20Bill%20of%20Rights%20Act%20-%20One-Pager.pdf

9. See: Tackling Unstable and Unpredictable Work Schedules: A Policy Brief on Guaranteed Minimum Hours and Reporting Pay Policies; (Center for Law and Social Policy, Retail Action Project, and Women Employed, 2014); Jon Messenger and Nikhil Ray. “The ‘deconstruction of part-time work” 2015 [op cit]. Indeed, some private companies implement their own minimum, such as 24 hours per week at CostCo.

10. “Why America Needs a $15 Minimum Wage.” Economic Policy Institute, February 2019. https://www.epi.org/publication/why-america- needs-a-15-minimum-wage/

11. “How the Paycheck Fairness Act will Strengthen the Equal Pay Act.” National Women’s Law Center, January 2019. https://nwlc- ciw49tixgw5lbab.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/How-the-Paycheck-Fairness-Act-will-Strengthen-the-EPA.pdf