Redefining Evidence-Based Practices: Expanding our View of Evidence

Introduction

Over the past 20 years, many youth-serving fields have become increasingly reliant on evidence-based practices (EBPs) when implementing and evaluating programs, especially in communities of color and in communities living in poverty. While EBPs can play a role in program development and practice, they lack cultural relevance and devalue other forms of knowledge, which perpetuates structural inequities. We must develop new standards of program implementation and evaluation that are both data driven and community informed. When we recognize lived experience as evidence and account for community and cultural context, we can elevate programs that work in the communities they serve, dismantling structural inequities.

How are EBPs Identified?

Evidence-based practices aim to ground programs and practices in demonstrably effective strategies and interventions by creating generalizable knowledge that can be applied regardless of context. Evidence-based practices are usually evaluated through:

- Randomized-control trials (RCTs)

- Rigorous systemic literature review

- Statistical meta-analysis

Systemic literature reviews and statistical meta-analyses are often informed by RCTs.

What are the Shortcomings of EBPs?

In generalizing knowledge, EBPs fail to consider the cultural relevance of practices, thereby failing to provide certain communities, especially communities of color, with solutions that respond to and understand their individual lived experiences and cultural contexts. An effective practice in one community may not be effective in all communities.

Shortcomings in the Development of RCTs

While randomized-controlled trials are recognized for their scientific rigor, the nature of how they are conducted is limiting for several reasons. RCTs do the following:

- Measure discrete, individual, and short-term outcomes: Individualistic metrics can’t measure for structural inequities that may be the root causes of disparities. RCTs frequently don’t measure change at the community level given practical, political, and ethical concerns; withholding promising interventions and resources from a control population can be unethical.

- Don’t study everyone and everything: Considering the resources required for RCTs, small and hard-to-reach communities are unlikely to be studied or consulted in the research process due to factors including small sample sizes and limited site-specific studies.

- Don’t have to be community driven: The researcher determines what questions to ask, what outcomes to measure, and who to study.

Shortcomings of the reliance on EBPs

- Lack cultural responsiveness: Relying solely on EBPs can devalue forms of knowledge and practice that can work in specific communities. EBPs typically don’t include cultural variables in research samples, don’t examine the impact of culture on outcomes, and don’t consider context and environment. Therefore, they fail to provide communities with solutions that could work well for them.

- Ignore broader social contexts and structures that shape people’s lives: Addressing root structural barriers requires systems change, not individual interventions.

- Must be standardized: Standardized interventions may be more effective if culturally framed and adapted, but once an EBP has been changed, it is no longer an EBP.

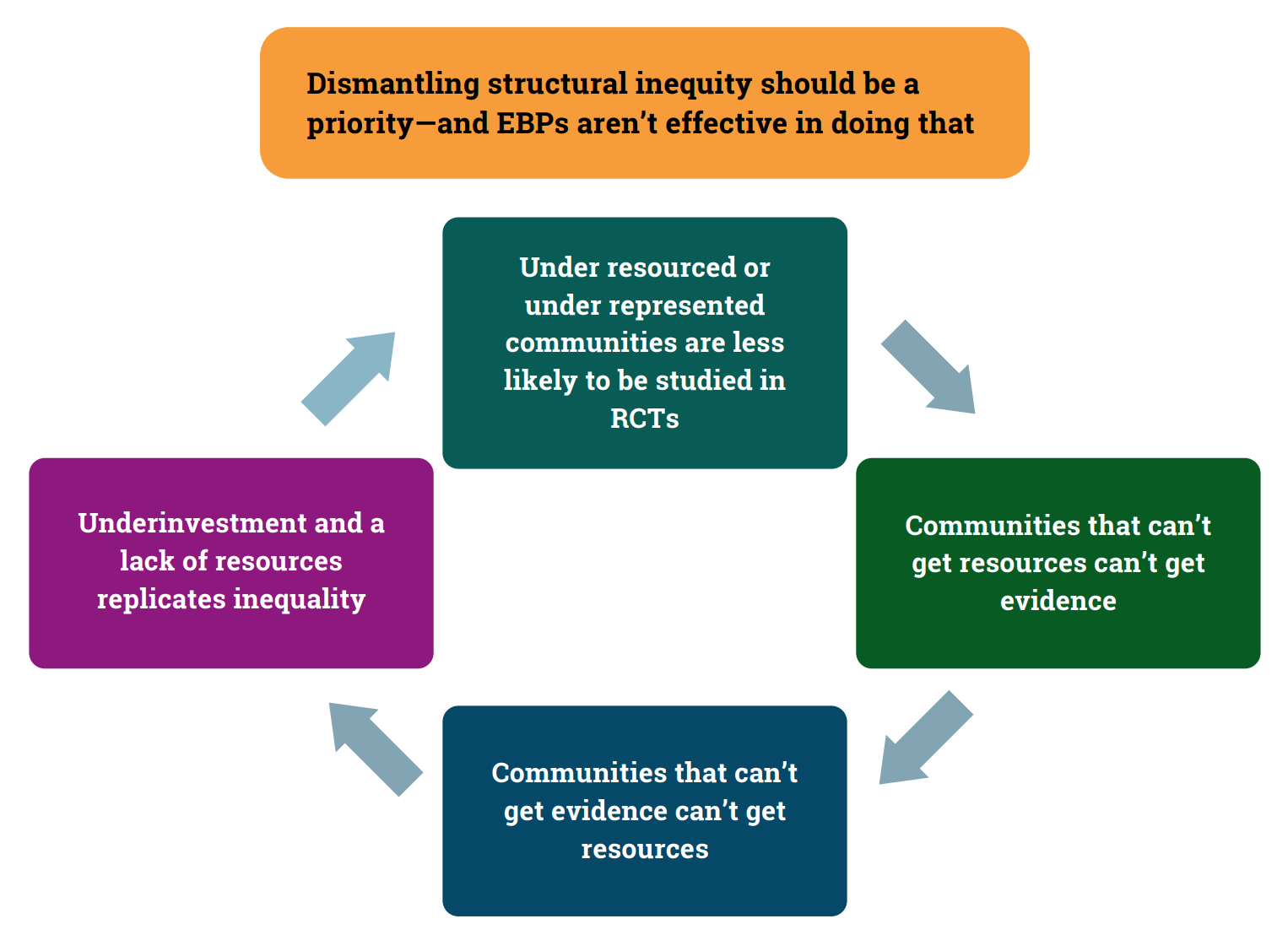

Relying Solely on EBP Perpetuates Inequity

What are Alternative Standards for Documenting Effective Programs and Practices?

Several communities and organizations have developed alternative evaluation standards that address cultural responsiveness and understanding. These standards should:

- Be informed by multiple sources of evidence, including quantitative and qualitative research, theory, practice, and evaluation;

- Allow those who implement the program to make changes and improvements based on what they are learning; and

- Understand that evidence based doesn’t have to be based in experimentation.

Practice-Based Evidence

One alternative standard is Practice-Based Evidence (PBE). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines PBE as “a range of treatment approaches and supports that are derived from, and supportive of, the positive culture of the local society and traditions.” These approaches:

- Are considered effective by local communities

- Are culturally embedded

- Have evolved over time to meet the needs of the community

- Have withstood the test of time

The Social Innovation Fund

The Social Innovation Fund (SIF) launched in 2010 as a White House Initiative. The SIF approach builds evidence by identifying promising community-based solutions and providing resources for rigorous evaluation to determine the effectiveness and replicability of those solutions.

The SIF combines PBE and EBP by:

- Identifying programs and practices that appear to be working

- Providing evaluation materials to confirm the results

- Determining if the solution can be scaled up, or if it is site specific

The SIF evaluates programs by:

- Documenting program outcomes

- Measuring the return on investment

- Evaluating the replicability of the program model

- Determining the feasibility of replication

- Measuring the feasibility of expanding the model to serve a larger population

The SIF categorizes practices in a tiered-evidence framework:

- Moderate evidence: Program received the desired outcome for a limited population

- Strong evidence: Program achieved the desired results and can be scaled up and applied to general populations

Community-Centered Evidence-Based Practice

Community-Centered Evidence-Based Practice (CCEBP) is an approach developed by the National Latin@ Network. It aims to bridge the gap between communityrelevant approaches and EBP, specifically regarding domestic violence prevention. It advocates for considering multiple sources of knowledge when making implementation decisions including:

- Community expertise

- Expertise of community practitioners

- Documented evidence

- Environmental and organizational context

The model weighs community expertise most heavily. Community expertise requires actively collaborating with the community in practice and implementation, along with actively engaging the community in decision making and documentation efforts.

Redefining EBP as data driven and community informed

Successful program implementation and evaluation should be both data driven and community informed. To do both successfully, programs need to move beyond decontextualized problems with generic interventions and instead create solutions that are based on individual, family, and community resources. Researchers and administrators should conduct interventions at the individual, community, and structural level that are centered on people and not problems. Until we recognize lived experience and other nonexperimental data as evidence, promising programs will continue to be under resourced, perpetuating inequity