Principles for a High-Quality Pre-Apprenticeship: A Model to Advance Equity

This brief by Noel Tieszen, Rosa García, Asha Banerjee, and Cameron Johnson contains framing, analysis, and recommendations for the development of high-quality pre-apprenticeship programs. Guided by an equity focus, these strategies can help to bolster the outcomes for individuals and communities that have been traditionally left out of apprenticeships.

Introduction

In the United States, apprenticeships have traditionally been considered the purview of the construction industry and a handful of other trades. But recent interest in developing nontraditional career paths has led to an expansion of apprenticeships into industries such as healthcare, childcare, advanced manufacturing, public safety, hospitality, information technology, cybersecurity, and more. For the many people who have been shut out of opportunities to enter or advance in these fields, this expansion holds great promise. Diverse pre-apprenticeships have the potential to help people access a career path that offers livable wages and benefits. These jobs are family-sustaining opportunities, supporting a worker and their family’s economic security.

As public investment in apprenticeships grows at both the federal and state levels, we must proactively ensure equitable access to these opportunities. Many of the same barriers that exclude people from other career pathways exist for apprenticeships as well. Pre-apprenticeship can be one tool to address some of these barriers– a stepping-stone that expands access to apprenticeships

This report outlines principles to guide federal, state, and local decision-makers and partners in developing equitable pre-apprenticeship programs and policy. These principles can mitigate the risk of investing in low-quality programs that lead to nowhere. This risk is especially high as the current Administration seeks to develop minimally regulated Industry Recognized Apprenticeship Programs (IRAPs), which would limit quality assurance and extend few labor protections to apprentices. Pre-apprenticeship policy must provide a framework of accessibility, quality, equity, and opportunity for advancement in family-sustaining careers. As Congress considers reauthorizing the National Apprenticeship Act and the Workforce Innovation Opportunity Act, it must seek to promote high-quality pre-apprenticeships, and the vitally important role they can play in helping to increase the participation of youth, women, people of color, immigrants, and formerly incarcerated individuals in Registered Apprenticeships. Federal and state policies must seek to reduce disparities and the historic inequality in the nation’s long-standing workforce and labor pipeline.

Developing actionable principles to promote equity

A critical step to advancing equity in pre-apprenticeships is to clearly define the key components of a highquality pre-apprenticeship—the principles we define below. To inform our best thinking on policy and practice in developing these principles, the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP) engaged a wide range of experts and thought leaders. They included advocates, policymakers, practitioners, and representatives from labor and industry. CLASP drew on their expertise in a series of interviews, an in-person convening, and several informal discussions (see p. 14 for a full list of participants)

The principles that follow are also informed by research studies conducted by other advocacy partners and thought leaders. For instance, Jobs for the Future’s Framework for a High-Quality Pre-Apprenticeship Principles for a High-Quality Pre-Apprenticeship Program1 outlines key elements of any pre-apprenticeship program. Our principles expand existing research as well as the program elements of quality pre-apprenticeships set out by the Department of Labor.

Our policy research involved examining:

- Program goals

- Integrating successful apprenticeship practices

- Program design, including equitable access, recruitment and placement

- Compensation

- Regional planning

- Pathways to postsecondary education

Our process centered people who face the greatest barriers to employment—communities that have been historically marginalized or left behind in apprenticeship systems and the workforce development system as a whole. We sought to identify ways to best serve them and lift the obstacles they experience. We hope our findings ensure that industry and government do not recreate the inequities of the past, but instead advance a pre-apprenticeship system that meets the needs of every community.

High-quality pre-apprenticeships can ensure equitable access to apprenticeship opportunities

Apprenticeship systems are not immune to the systems of power that have embedded inequity in other training or employment pathways and society at large. In 1967, Cornell University published a study titled “Remedies for Discrimination in Apprenticeship Programs.”2 The study described overwhelming resistance to gender and racial integration in apprenticeship programs in building, machinist, and printing trades. Researchers from Cornell and the University of Texas documented policies and practices that maintained almost total power among white men.

Today, outright discrimination in policy and practice remains in place. Systemic barriers to access and dayto-day effects of broader social inequity continue to prevent many people from participating in apprenticeships and earning the rewards of apprenticeable careers. Those who face the greatest hurdles include people of color, youth, people who are immigrants, people with disabilities, women, and others.3

Who participates in apprenticeship programs? And how do they fare?

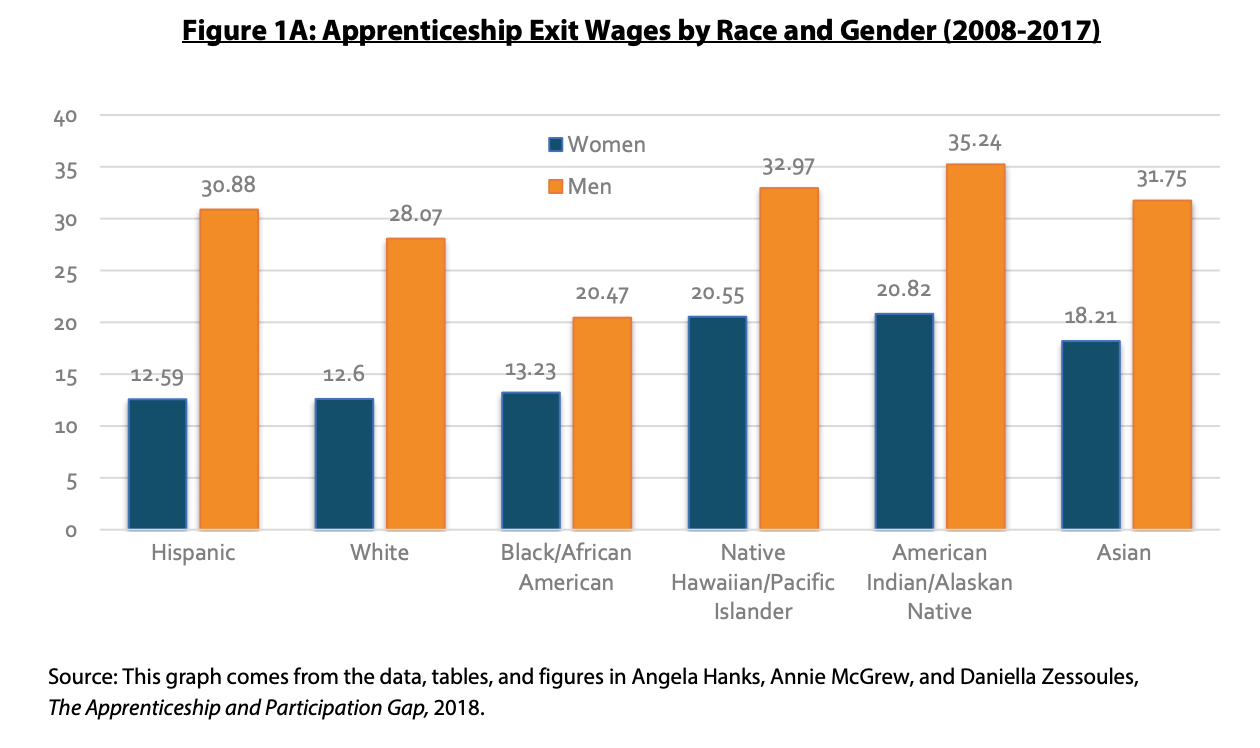

As of 2017, 7.3% of apprentices nationwide were women – an increase of approximately 1% over the previous decade. However, wages for women remain much lower than for men. This is due in part to occupational differences: women are most likely to be enrolled in apprenticeships with lower pay scales. For example, the top occupation for female apprentices from 2008-2017 was childcare development specialist, where median wage for a journeyperson (someone who has completed an apprenticeship) was only $9.75/hour. In contrast, the top occupation for male apprentices was electrician, where median journeyperson wage was $23.46.4

Apprenticeship participation data by race is more difficult to assess given inconsistent and incomplete reporting by apprenticeship programs and apprentices themselves. Available data seems to suggest that participation rates for Black and Latinx apprentices are similar to their participation in the labor force as a whole.

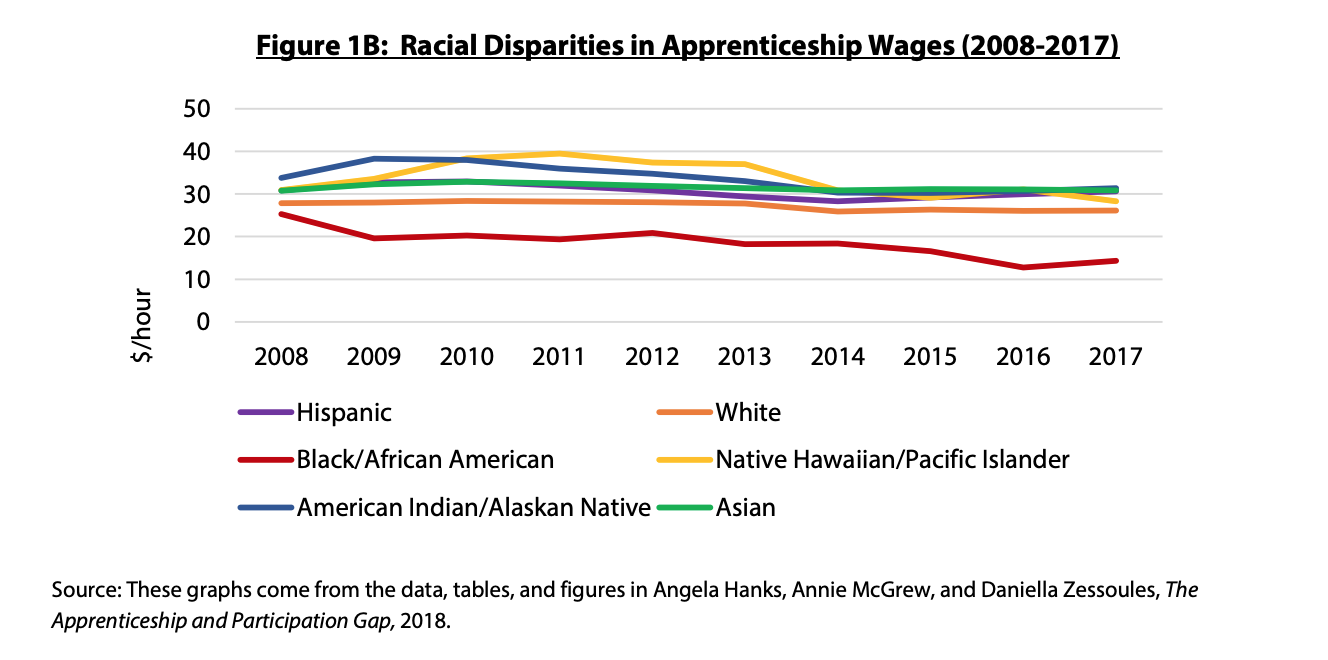

However, there are stark racial wage disparities among apprentices—gaps that are even greater when they are disaggregated by gender (see figures 1A and 1B). Some of these differences may be attributable to factors such as participation trends in various industries or regions of the country. But a closer look at data shows that wages have been consistently lower for Latinx women, compared to women from other races. Furthermore, Black apprentices receive lower wages than any other racial or ethnic group.

This is explained in part by our country’s continuing history of mass incarceration of African American people. Disproportionate numbers of African American apprentices are incarcerated. In fact, 25 percent of all Black apprentices completed their apprenticeships during incarceration. This suggests that African Americans have disproportionately low access to apprenticeships outside prison.

The quality and long-term outcomes of apprenticeships in prisons rarely match those of Registered Apprenticeships on the outside. Prisons and their employer partners are able to operate Registered Apprenticeships without offering the labor protections and minimum wages required for any other workers in the United States. For example, the median wage of incarcerated apprentices is 35 cents an hour. Apprenticeships in prisons are likely to be disrupted by transfers to other facilities or other obstacles imposed by the prison system. In addition, since these apprentices work within the prison walls, they are rarely able to continue employment upon their release. Even for those who complete a Registered Apprenticeship while incarcerated, criminal records, probation/parole requirements, and other factors hamper their access to employment and wage growth when they come home.

What is a pre-apprenticeship?

What is a pre-apprenticeship?

At its most basic level, pre-apprenticeship is a preparatory experience that precedes participation in an apprenticeship. The U.S. Department of Labor defines pre-apprenticeship as “a program or set of strategies designed to prepare individuals to enter and succeed in a Registered Apprenticeship program and has a documented partnership with at least one, if not more, Registered Apprenticeship program(s).”5 Unlike other kinds of career prep experiences, job readiness programs, or standalone trainings, a preapprenticeship is part of a larger apprenticeship system.

Bipartisan support for apprenticeship models has indirectly raised the profile of pre-apprenticeship, yet this term is often used to describe a range of programs that stretches far beyond its definition. Further complicating matters, many erroneously use the terms “youth apprenticeship6 ” and “pre-apprenticeship” interchangeably. Fundamentally, a pre-apprenticeship is a preparatory experience that leads to participation in a Registered Apprenticeship, regardless of a worker’s age.

Principles to design high-quality, equitable preapprenticeships

Pre-apprenticeships are not a panacea. But if they are done well – properly designed and funded – they can unlock pathways to careers and industries historically denied to many people of color, immigrants, and women. These career paths can lead to family-sustaining jobs with benefits and help low-income people move out of poverty

One way to expand the participation of historically marginalized groups in Registered Apprenticeships is through high-quality preapprenticeships.

The following principles serve as a guide to reaching that goal.

1. Beginning with the end in mind: Establishing program goals

It is vital to consider how any equity strategy interacts with the systems of power it functions within. This includes identifying whether barriers are structural, political, geographic, or financial. Preapprenticeship is one potential strategy that can be used to address a variety of barriers to equity in apprenticeship systems. It is important to ask: to what extent are these barriers inherent to the apprenticeship model, endemic in some apprenticeship systems, or imposed externally? Then the most appropriate program goals can be established.

Potential program goals for a pre-apprenticeship:

- Increasing access to family-sustaining career paths for youth, low-wage workers, and adults who face barriers to employment

- Preparing potential apprentices to pass entrance exams

- Diversifying the workforce in an industry

- Improving apprenticeship retention and completion rates

- Providing wraparound supports for potential apprentices, such as child care, transportation, etc.

- Filling vacant apprenticeship slots

1 JFF’S Framework for a High-Quality Pre-Apprenticeship Program, JFF Center for Apprenticeship and Work-Based Learning, 2019. https://center4apprenticeship.jff.org/apprenticeship/preapprenticeship/

2 F. Ray Marshall and Vernon Briggs Jr., Remedies for Discrimination in Apprenticeship Programs, Cornell University ILR School, 1967. https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1134&c…

3 Oftentimes, communities of color can be funneled towards certain kinds of apprenticeships with limited opportunities for growth and earning potential. An equitable pre-apprenticeship should gauge whether a particular student is better suited for a postsecondary opportunity or an apprenticeship opportunity. When determining the latter, officials should intentionally consider a wide range of both traditional and non-traditional pathways, including those in emerging sectors, such as healthcare, information technology, and other STEM fields.

4 Angela Hanks, Annie McGrew, and Daniella Zessoules, The Apprenticeship Wage and Participation Gap, Center for American Progress, 2018. https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2018/07/10122156/Appren…. Figures 1A and 1B are also adapted from this paper.

5 Training and Employment Notice No. 13-12 of November 30, 2012, Defining a Quality Pre-Apprenticeship Program and Related Tools and Resources, https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/TEN/TEN_13-12.pdf.

6 “Youth apprenticeship” refers specifically to apprenticeships that are designed for students to begin while they are in high school. The Partnership to Advance Youth Apprenticeship (PAYA) outlines principles of quality youth apprenticeship, which can be found here: https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/partnership-advanceyouth-app…

7 Training and Employment Guidance Letter WIOA No. 13-16 of January 12, 2017, Operating Guidance for the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, Guidance on Registered Apprenticeship Provisions and Opportunities in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), https://wdr.doleta.gov/directives/attach/TEGL/TEGL_13- 16.pdf.

8 National portable credentials are trusted by employers and educational institutions. Every graduate of a Registered Apprenticeship program receives a nationally-recognized credential, referred to as a Certificate of Completion, which is issued by the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL) or a federally recognized state apprenticeship agency. This portable credential signifies that the apprentice is fully qualified to successfully perform an occupation. See TEGL 13-16.

9 These programs may not be feasible or appropriate for some pre-apprenticeships For example, some short-term programs may not provide enough time for students to even register and sit for exams, let alone gain academic, language, or test-taking skills sufficient enough to boost scores. However, employers and sponsors can develop partnerships with local providers, such as Adult High Schools, community-based organizations, and community colleges – entities that offer these educational services, often at a relatively low cost or for free.

10 Members of communities that have been shut out or underrepresented in an industry may have minimal familiarity with related career paths that others with family history or community proximity may take for granted.

11 TEGL 13-16.

12 Food and Nutrition Service, “SNAP Work Requirements,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, May 29, 2019, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/work-requirements.

13 Congress established the Section 3 policy to guarantee that the employment and other economic opportunities created by Federal financial assistance for housing and community development programs should, if possible, be directed toward low- and very-low income persons, particularly those who are recipients of government assistance for housing. Section 3 residents are public housing residents and low and very-low income persons who live in the metropolitan area or non-metropolitan county where a HUD-assisted project for housing or community development is located. https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/section3/sect…