Between the Lines: Understanding Our Country’s Racialized Response to the Opioid Overdose Epidemic

The increase in opioid use and overdose is a hot topic of conversation, playing out in different ways — often with the top-line narrative that policymakers aren’t doing enough. CLASP recognizes that responses are more public health-focused when white populations are reported to be using drugs, and more punitive when substance users are reported to be people of color.

The opioid overdose and general substance use responses are not reaching communities of color. Now that the current opioid overdose epidemic is impacting mostly white, rural populations, policymakers are feeling significant political and social pressure to do something about it.

The Center for Law and Social Policy’s (CLASP’s) mental health work focuses on the design of systems and policies in the health system and the affect of race and ethnicity on how a person interacts with the health system and receives services. Over the following pages, we provide an overview of how history and the response to the opioid overdose epidemic play a part in widening health inequities, and what we need to do about it.

Unless we figure out how to make significant upstream economic and policy changes, we will continue to see inequities in prevention, screening, and treatment, resulting in greater racial disparities in opioid overdose and substance use disorders (SUD) overall.

The report is divided into six sections:

1. Defining the Context: How implicit bias impacts who receives opioid prescriptions and why drug overdose deaths for communities of color in poverty are increasing.

2. How the Racial Wealth Gap and Poverty Contribute to the Epidemic: Racist policies, economic disparity, and the flooding of drugs to communities of color living in poverty are all connected.

3. Historical Racial Bias Impacts on Drug Enforcement: Since the 1800s, laws have existed criminalizing communities of color due to the narrative associating Black people with drugs, when both white and Black communities were using drugs. Communities of color continue to feel the effects of the War on Drugs and related punitive laws to this day.

4. Differences in Response, Access to Treatment: Treatment is often based on insurance, proximity to services, whether someone is incarcerated or not, the availability of culturally responsive providers, and one’s willingness to seek care. Effective treatment provision depends on the provider, and if substance use is criminalized in a jurisdiction or not.

5. The Federal Response: Policymakers increased funding to address opioid overdoses affecting white and rural communities, giving priority to areas where federal datasets show high rates of overdose, but may not capture overdoses in Black and Brown communities. Resource-poor communities, often including communities of color, have a much harder time getting funding and resources.

6. Recommendations, Strategies: Truly addressing the opioid overdose epidemic for communities of color involves major policy and system changes, reversing damaging effects of past policies and narratives.

Overview

The opioid overdose epidemic exposes lines drawn around perceived racial identities and across socioeconomic status.

Because of opioid overdose rates in white people, policymakers have responded to the resounding and repeated narrative that the epidemic primarily affects white people. They have focused funding efforts in white communities, while neglecting and further criminalizing communities of color for general substance use.

This report provides a different perspective to the predominant discussion by outlining how harmful policies weakened infrastructures, using race as a tool. This weakening has caused opioid overdoses to increase. Without critically examining the response of policy makers, inequities between rich and poor, people of color and white, will continue to increase. To think about the large-scale solutions necessary to help communities receive the supports they need to thrive, we must look beyond opioids to substance use more broadly.

Historical racism, implicit racial bias, and discrimination have shaped the response mechanisms of the past, and unfortunately are a part of the responses we see today. Rather than providing communities of color with treatment/resources, policies criminalize these communities, resulting in disproportionate suffering from drug epidemics. The effects of criminalization are lasting—-affecting individuals’ ability to get employment, education, housing, or even vote. These detrimental policies erode the foundation of entire neighborhoods, destabilizing economic stability, mobility, and complete infrastructures.

Without major systemic and policy changes that address the root causes preventing all communities, particularly in communities of color, from reaching true economic justice, there cannot be health equity. In developing strategies to curb the opioid epidemic, policymakers and advocates must consider the complexities of behavioral health issues that communities of color experience and combat historical racial bias within the health and criminal justice sectors.

Defining the Context

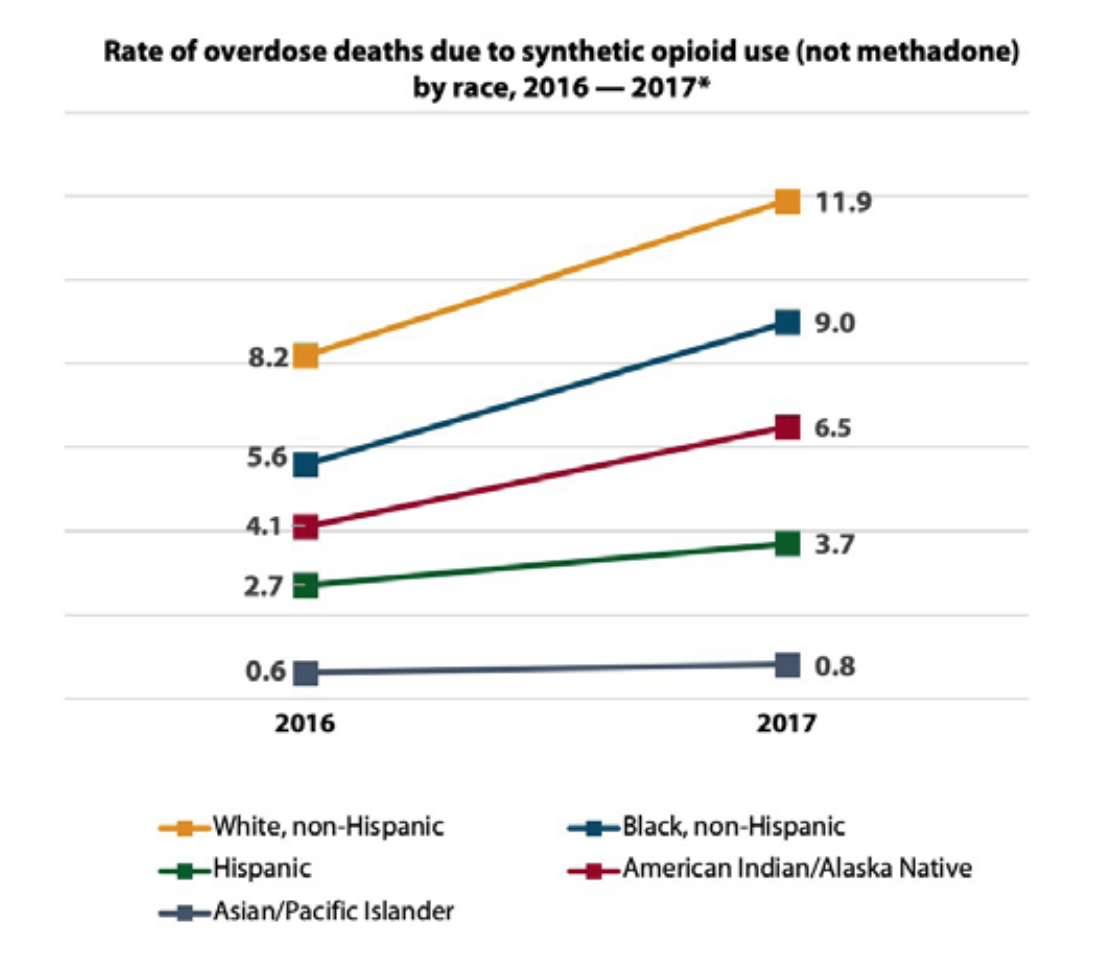

In the opioid overdose epidemic, death rates have risen for all populations, including African-American, Latino, Native, and Asian-American and Pacific Islander populations. Although the highest overdose death rates are in White people in the United States, death rates for particular communities of color are on the rise.

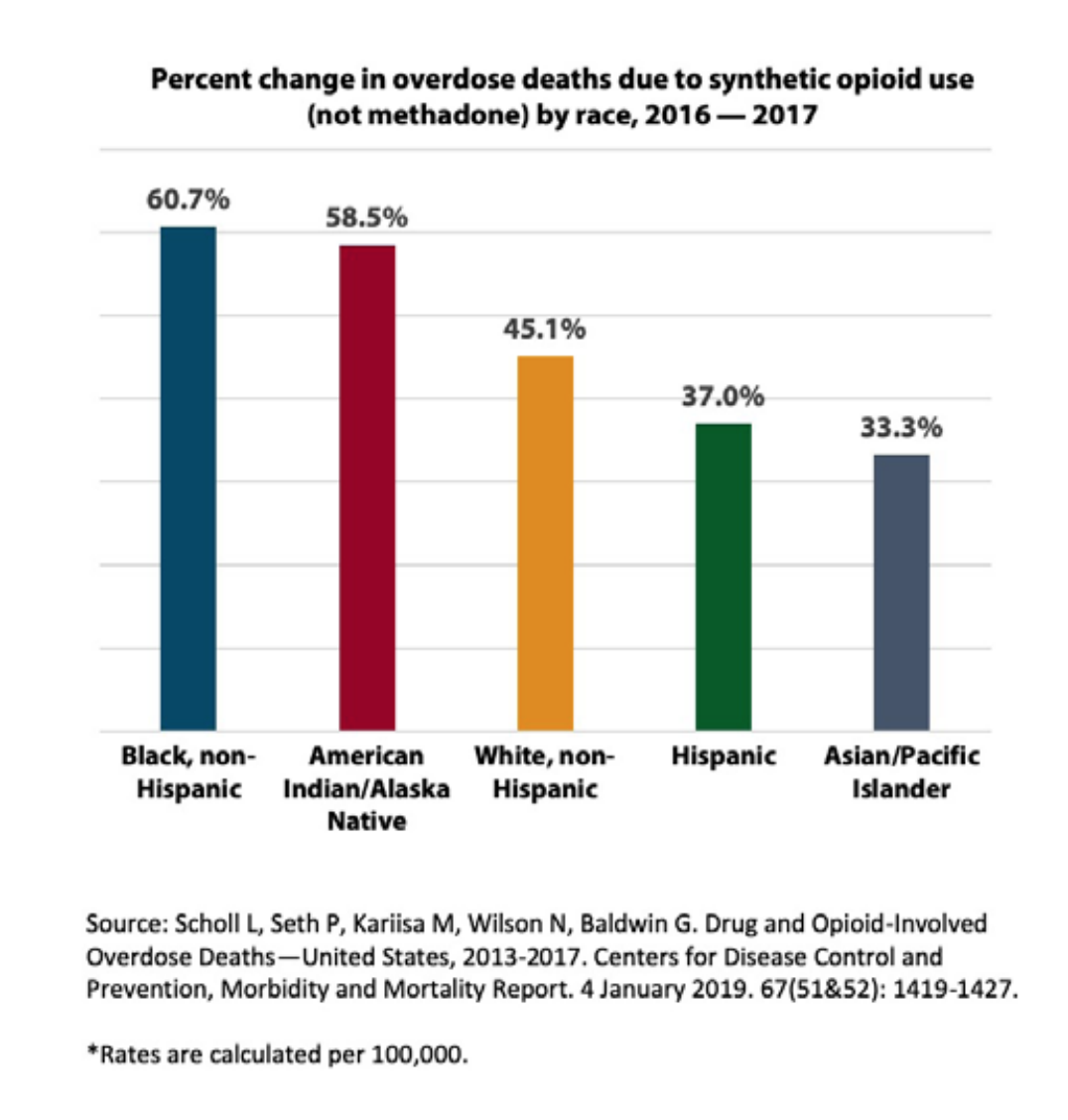

From 2016 to 2017, the most recent data available, the opioid overdose death rate increased the highest for Black people at 25.2 percent, followed by American Indian/ Alaska Native (AI/AN) people1 at an increase of 12.9 percent. The highest death rate increases from synthetic opioids over the same timeframe were for Black people at 60.7 percent and for AI/AN people at 58.5 percent.2

Opioid deaths are rising annually due to an increase in the availability of prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic fentanyl.3, 4 In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that prescription opioid addiction reached epidemic heights. The lack of belief that substance use was linked to health issues, limited access to opioid treatment programs, limited rehab facilities, a sense of hopelessness, trauma, and lack of education on the dangers of opioids are likely contributing factors to the opioid death toll.

States with higher poverty levels had disproportionately worse rates of overdose deaths from prescribed opioid drugs. CDC data from 2002 to 2013 shows that heroin use increased nearly 77 percent in households with an average income of $20,000- 49,000 and 62 percent in households with an average income of under $20,000. Less than 5 percent of those individuals had Medicaid coverage, and around 5 percent had no insurance coverage.5

The opioid epidemic harms many communities living in concentrated levels of poverty, often in communities of color. This makes those who already experience trauma and toxic stress vulnerable.6 Deep concentrations of poverty are often caused by racist and discriminatory policies in housing, immigration, barriers to public benefits, as well as limited access to jobs, food, and other opportunities to help communities thrive. Threats and instability also define the impact on communities because of policies like the “War on Drugs,” placing many young men of color in prison for minor substance infractions, including possession. These factors contribute to the isolation and negative conditions that open the door for substance overuse. Harmful policies lead to broken neighborhood infrastructures, which prevent communities from receiving adequate and effective treatment, causing long-term economic and health concerns for communities living in poverty.

Researchers link implicit racial bias, disparate access to health insurance, and variable access to treatment centers as contributing factors to the over-prescription of opioids in white communities compared to communities of color.7 However, national datasets may not be capturing the entire picture of substance use and overdose among people of color, leading to misleading narratives. Use of non-prescription opioids versus those provided through a prescription in communities of color may be underreported through existing data collection mechanisms and processes. The ways in which questions are asked, if at all, and locations where people are interviewed may create additional barriers from understanding true rates in overuse.

The discrimination and stigma around people of color led and continues to lead, as recently as a 2016 survey of providers, to the misperception that Black people have a higher pain tolerance than white counterparts.8 Misconceptions about how thick Black people’s skin was compared to white people’s skin date centuries back in America’s history. Some providers do not prescribe opioids to people of color and ultimately leave them on their own to seek pain relief without any treatments to combat the severe effects of opioids. Additionally, physicians taught and practicing through a traditional American medical lens may screen for pain using a numeric scale, although some ethnicities (e.g., Native populations) may not be able to translate their level of pain on such a scale. This may prevent providers from giving prescriptions for pain medications when they might otherwise do so.9