CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy

This statement can be attributed to Wendy Chun-Hoon, president and executive director of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)

January 7, 2026, Washington, D.C. – Today’s shooting of an unarmed woman by ICE agents in Minneapolis is only the latest tragic fatality to result from the Trump Administration’s aggressive and reckless immigration enforcement activities. The 37-year-old was killed as ICE was launching a crackdown that surged approximately 2,000 agents into the city. As a direct result of ICE activity, yet another person was needlessly ripped away from their loved ones and community because of the actions of this administration.

On the first day of President Trump’s second term, he signed an executive order beginning his deportation agenda, including strengthening the capacity for officers to conduct immigration enforcement actions with little to no limitations and increasing collaboration between Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and local police officers. The administration and Congress have given, and continue to give, ICE exorbitant resources to conduct indiscriminate immigration enforcement in the name of “safety,” but the reality is these policies have devastating consequences for communities, regardless of immigration status.

The evidence of harm since the beginning of Trump’s second term is clear: this is not the first fatal shooting since January 20, 2025, thousands more have been deported (including U.S. citizens), a record number of people have died in ICE detention, families have been torn apart, and entire communities have been thrust into confusion and chaos.

The administration’s crusade against immigrants has violent and deadly consequences. We must reject ICE’s deportation and terrorism campaign if we want our communities to be truly safe.

As an organization advocating for immigrant children and their families, CLASP abhors this tragedy and calls for Congress and state and local officials to hold this administration accountable for the irreversible harm they have caused.

Washington, D.C., January 5, 2026 — Last week, an ill-informed YouTube “influencer” accused child care centers run by Somali providers in Minnesota of fraud. In response to these accusations and without any further investigation, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) took immediate actions to freeze federal child care funding for Minnesota, to implement a “Defend the Spend” effort for all states, and to establish a fraud reporting website and hotline. Since then, numerous “influencers” have made similar claims against child care providers in other states.

Stephanie Schmit, Director of Child Care and Early Education at the Center for Law and Social Policy, said, “It is hard to see this as anything but politically motivated attacks on child care providers and reactions that will punish children and families nationwide. Child care providers of diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds offer critical, culturally competent care that meets the unique needs of the children and families in their communities across the country.”

The Child Care and Development Fund is a lifeline for families with low incomes to access stable and reliable child care so they can go to work. Disruptions to this essential funding will only harm children, families, and providers.

While HHS has not yet released information about how it will implement “Defend the Spend,” the very brief implementation of the program in April resulted in delayed payments to states. This created barriers for families because providers, who operate on razor-thin margins, depend on timely payments from the states to run their programs. Because additional information has not yet been released, there is significant confusion and worry about the impact that this might have.

“Child care providers and state child care agency staff already put a lot of effort and energy into reporting how they spend their resources. Adding further reporting requirements to their overburdened workload will take their time and attention away from where it should be–focused on providing the best care possible for children,” Schmit said.

It is troubling that a federal agency would make such a destabilizing decision based on the unfounded claims of an “influencer” with a long history of videos that prioritize shock over facts. HHS should consider the actual impacts of any requirements on children, families, and providers, and make decisions accordingly.

[EXCERPT]

Immigrants are essential to the care workforce, making up 20% of child care workers, including 26% of center-based child care providers and early educators, and 23% of preschool teachers, according to the Center for Law and Social Policy.

Read the full article on StatePoint Media here.

Note: this article was published by media outlets nationwide.

One hundred, ninety organizations concerned with the well-being of children submitted a public comment to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) opposing a proposed rule that would provide the agency discretion to deny green cards based on factors such as an applicant’s health or use of any federal health or social services program.

By Madeline Mitchell

[EXCERPT]

Suma Setty, senior immigration policy analyst for The Center for Law and Social Policy, a nonprofit policy think tank in Washington, D.C., says child care providers have also lost some of their workers with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) “because of fears of immigration enforcement.” DACA is a government program that allows for work authorization and puts a temporary hold on deportation for those who were brought into the country illegally as children.

Read the full article in USA Today here.

Note: This article was republished by scores of media outlets across the country.

By Monica Potts

[EXCERPT]

But the two biggest factors coming into play that are hitting families especially hard heading into the new year are the costs of childcare and health care, said Ashley Burnside, a senior policy analyst at the Center for Law and Social Policy, or CLASP. “We can’t talk about affordability in this moment without naming the huge health care costs that families are now facing because of the expiration of the premium tax credits,” she said.

…

Lorena Roque, associate director for labor policy at CLASP, said she sees data showing that a lot of families are taking on two or more jobs just to make ends meet. But even that might no longer provide a full picture of who is struggling because the administration has been hostile to the kinds of data-gathering efforts that would give us a fuller picture of the economy, like the rates of Black and Latino unemployment.

Read the full article in The New Republic.

By Jireh Deng

[EXCERPT]

Earlier this year, the Department of Government Efficiency slashed funding for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, shuttering local oversight offices—a move that the Center for Law and Social Policy described as an “imminent threat to all workers.”

Read the article in Sierra Magazine here.

By Christian Collins

The Student Compensation and Opportunity through Rights and Endorsements (SCORE) Act, H.R.4312, is a prominent example of the dangers in crafting broad legislation based on outliers instead of on the common experiences of students. Though the SCORE Act is a dedicated effort from Congress to punish college athletes for seeking the ability to be compensated for the labor they provide, this is not the first bill this year to directly target college athletes. H.R. 1, the reconciliation bill passed in July, includes a provision that removes Pell grant eligibility for any student receiving non-federal aid that equals or exceeds their full cost of attendance. This means that starting in fall 2026, every full-ride scholarship athlete across all college sports will be ineligible for Pell Grants:

“(6) Exclusion.—Beginning on July 1, 2026, and not withstanding this subsection or subsection (b), a student shall not be eligible for a Federal Pell Grant under subsection (b) during any period for which the student receives grant aid from non-Federal sources, including States, institutions of higher education, or private sources, in an amount that equals or exceeds the student’s cost of attendance for such period.”

The SCORE Act and Reconciliation Bill Limit College Affordability Pathways for College Athletes

For schools that opted into the House v. NCAA settlement, NCAA Division 1 level sports are now all treated as “equivalency” sports regarding the financial aid offers given to athletes. The term “equivalency” means that scholarships are allowed to be divided into partial scholarships split among multiple athletes. Prior to the settlement, six sports were deemed as “headcount” sports where only full-ride scholarships could be allocated: football and basketball for men’s programs, and basketball, volleyball, tennis, and gymnastics for women’s programs.

Fifty-four institutions decided not to opt into the House settlement, which means that the old system of “headcount” versus “equivalency” sports remains in place. But beginning next year, every football and men’s basketball player attending one of those 54 institutions will lose Pell Grant eligibility. For the nation’s remaining 311 Division 1 institutions, as of fall 2026, their athletes will have to choose between receiving a full athletic scholarship or having access to Pell Grants.

The Impact of this Pell Grant Provision Will Disproportionately Affect Black Men

Access to Pell Grants, even for students who receive full scholarships through athletics, is critical for students with lower incomes to fund out-of-classroom expenses not covered by scholarships, including transportation, child care, and classroom supplies.

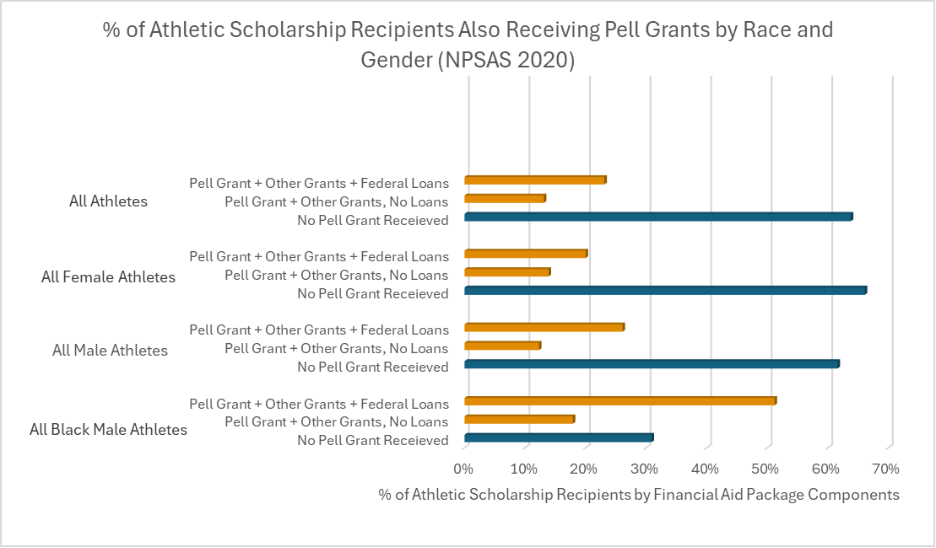

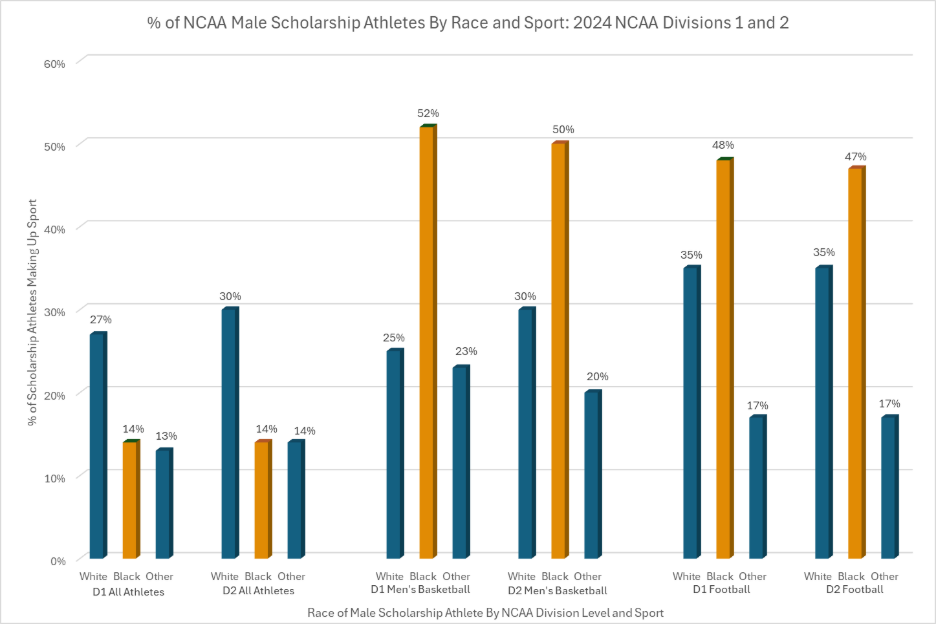

This provision is almost surgically targeted at Black male students who participate in athletics due to the rates that they qualify for Pell Grants compared to other demographics. From the latest National Postsecondary Student Aid Survey data, nearly 69 percent of Black male college athletes on athletic scholarship received Pell Grant awards, compared to 53 percent of all Black male students and just 36 percent of all college athletes. Football and men’s basketball, the former two “headcount” sports which have the historical precedent of athletes being offered full-ride scholarships to participate in those programs and are the highest-revenue generating programs among all college sports, are represented by majorities and pluralities, respectively, of Black men.

In their rush to guarantee the ability of institutions and third parties to profit off the labor of college athletes without consequence, the authors of the SCORE Act are sandwiching primarily Black male students into a cost-of-attendance trap. These athletes will now be forced to use revenue share payments and name, image, and likeness (NIL) deals to make up for losing Pell Grant dollars. Revenue share payments are currently capped, with schools also refusing to share publicly how much athletes are receiving from these payments or if they’re receiving payments at all. NIL deals are rare for most athletes and purposefully being delayed by institutions via the College Sports Commission, so even if athletes successfully land a deal, there’s no guarantee they get the money in a timely manner.

In their rush to guarantee the ability of institutions and third parties to profit off the labor of college athletes without consequence, the authors of the SCORE Act are sandwiching primarily Black male students into a cost-of-attendance trap. These athletes will now be forced to use revenue share payments and name, image, and likeness (NIL) deals to make up for losing Pell Grant dollars. Revenue share payments are currently capped, with schools also refusing to share publicly how much athletes are receiving from these payments or if they’re receiving payments at all. NIL deals are rare for most athletes and purposefully being delayed by institutions via the College Sports Commission, so even if athletes successfully land a deal, there’s no guarantee they get the money in a timely manner.

Though the average disclosed NIL deal for Division 1 football and men’s basketball players through 2025 is $6,112, nearly 66 percent of all NIL deals for these athletes are worth $1,000 or less, which is nowhere near what athletes stand to lose in Pell Grant awards.

Though the average disclosed NIL deal for Division 1 football and men’s basketball players through 2025 is $6,112, nearly 66 percent of all NIL deals for these athletes are worth $1,000 or less, which is nowhere near what athletes stand to lose in Pell Grant awards.

Fixing College Athletics Requires Giving and Taking, But Congress Is Only Taking from Students

The flawed logic behind the Pell Grant reconciliation provision—that athletes are now able to earn enough money through NIL deals and revenue sharing payments to not need Pell Grants—is the exact same flawed logic behind the SCORE Act provisions that clamp down on total compensation and federal labor protections of college athletes.

Federal policymakers have two immediate pathways to reverse their present course of forcing college athletes to seek rare third-party generosity to afford cost-of-living expenses. One pathway can be exercised by the executive branch, which should provide clarity on how the Pell Grant changes within H.R. 1 will be enforced by using the upcoming negotiated rulemaking sessions led by the Accountability in Higher Education and Access through Demand-driven Workforce Pell Committee. The other is for Congress to craft legislation that truly supports athletes, which requires centering these students in the policy creation process to understand their actual circumstances.

Op-Ed by Jesse Fairbanks, Kaelin Rapport, and Isha Weerasinghe

[EXCERPT]

In early September, officials in Utah announced a plan to build an encampment just outside Salt Lake City where up to 1,300 people experiencing homelessness would be forced to receive treatment for mental health challenges. Unhoused people who refuse to stay in this state-run facility could instead end up in jail.

Forcing people to relocate to a facility described by its advocates as a “homeless campus” is a violation of their civil liberties. To make matters worse, this approach is generally ineffective and prone to bias. Research has shown that involuntary commitment disproportionately affects people of color and disabled people. And in many cases, the care provided to those the involuntary committed is not sufficient to meet their mental health needs.

Read the full op-ed in The Progressive.

NOTE: This op-ed, which was originally published in The Progressive, was syndicated and republished by media outlets nationwide, including in Miami, FL; Bradenton, FL; Columbia, SC; Hilton Head, SC; Myrtle Beach, SC; Rock Hill, SC; Durham, NC; Charlotte, NC; Raleigh, NC; Columbus, GA; Chattanooga, TN; Lexington, KY; Schenectady, NY; Pittsburgh, PA; State College, PA; Kansas City, KS; Fort Worth, TX; Bellingham, WA; Tacoma, WA; Olympia, WA; Boise, ID; Merced. CA; Modesto, CA; Fresno, CA; San Luis Obispo, CA; and Sacramento, CA. It was also picked up by national outlets including MSN, NewsBreak, and ArcaMax.

By Christian Collins

The Student Compensation and Opportunity through Rights and Endorsements (SCORE) Act, H.R.4312, is the culmination of a multiyear effort from colleges and universities to preserve an outdated and unjust economic system. Following the landmark House v. NCAA federal antitrust settlement, which brought roughly $2.8 billion in back damages to former college athletes from uncompensated labor and established the first revenue-sharing model for institutions to directly pay students for athletic labor, Congress is attempting to permanently wipe out those hard-fought gains.

The SCORE Act conflates two distinct issues: the inequitable state of college athletics and the financial insecurity of institutions due to federal funding cuts. Taking rights away from students won’t solve either issue. This legislation is just an attempt by Congress to pass the blame from its own inaction onto students who are only seeking the right to be paid for their labor.

Seeking to comprehensively address inequities in college athletics is no excuse to codify the greed of institutions into federal law. The SCORE Act doesn’t create a more equitable college athletics system; rather, in its current form, it contains multiple provisions that directly harm college students by preserving the ability of institutions to profit off them without fair compensation, including:

- An antitrust exemption protecting institutions from liability for collusion to limit earnings of college athletes and their ability to freely transfer schools.

- Permanently barring college athletes from employment status, which prevents students from being protected by federal employment law.

- Preserving the ability of institutions to charge students athletic fees. This is a common practice; Division 1 Football Bowl Subdivision schools alone raised $668.5 million this way in 2023. The bill bans this practice only for institutions that earn more than $50 million in annual media revenue from athletics, which applies to less than 1 percent of all Title IV colleges and universities across the country.

- Pre-emption of existing state laws related to college athletics, which is a likely constitutional overreach by Congress going beyond its current legal jurisdiction over public education.

The SCORE Act’s Narrow Perspective Will Have Widespread Consequences

The bill’s primary objective is to deny college athletes basic federal labor protections and codify severe economic restrictions on current and future athletes that no other students on campus face. From smaller private schools that utilize athletic programs as an enrollment tool to large public universities that use athletics as public marketing and donor engagement opportunities, the labor of athletes extends far beyond their time on the field. Instead of providing additional protection for students from harassment and abuse brought by gamblers, preventing states from relying on gambling taxes to make up for larger federal funding shortfalls and fund athletic programs, and how institutions often spend more on coaching and staff compensation than on all financial aid for athletes, Congress has used the SCORE Act to prioritize allowing schools to pay their own students as little as legally possible.

Concerningly, the authors of this bill failed to address the racialized impact it would have on marginalized students, especially Black men. The SCORE Act undercuts the notion that college athletics are a primary driver of socioeconomic mobility for young Black men, who represent majorities and pluralities of athletes competing in the highest revenue-generating sports (football and men’s basketball) across Divisions 1 and 2. This bill would codify academic institutions being able to reap billions in annual revenue from the uncompensated labor of Black students through a “plantation” economy, but not having to support their academic and professional development.

The SCORE Act Would Protect Institutions from the Consequences of Exploiting Their Own Students

Limiting the income potential of, and labor protections for, student workers on college campuses only signals that institutions care more about what money they can extract from students versus how they can best educate students. Institutions have made no complaints over the rampant revenue generation and athletics-related spending that they’ve embarked on for years, but are now begging Congress to stop athletes from receiving a fair share.

The SCORE Act is an attempt by a small subset of universities to preserve an inequitable economic system due to pure greed. Members of Congress should oppose this legislation and instead work to advance policies that support students by crafting legislation that includes the following provisions:

- Guaranteed collective bargaining rights and employment status for college athletes.

- Federally guaranteed health and safety standards for athletes regardless of competition level.

- Prohibiting public institutions from entering financial relationships with gambling companies, along with increased protections for students from being harassed by gamblers.

- Increasing federal spending on higher education so that states aren’t incentivized to promote sports gambling for fiscal sustainability.

Other CLASP publications on the exploitation of Black male college athletes include: