CLASP

The Center for Law and Social Policy

By Lily Ana Marquez

1. What motivates me to show up as a parent leader and advocate?

1. What motivates me to show up as a parent leader and advocate?

Being the parent of two children who are very different motivates me to continue as a parent leader and a strong advocate. It is my responsibility to ensure they and all children have what they need to thrive. I show up as a leader and advocate because my children still need someone to pave the way, to speak up when they can’t, and to influence systems that directly affect their lives. I believe that policies should be created by parents or in collaboration with them, so they reflect the real needs and experiences of families. My motivation is rooted in keeping my children’s well-being at the forefront of every decision and working toward a future where all families are seen, heard, and supported. Therefore, parents need to be involved in the well-being of their children by being present, engaged, and showing up when important decisions are made affecting their lives. Children and families have different needs; therefore, policies and systems need to change to reflect the needs of their constituents, making sure no one is left behind. If a child has what they need emotionally, intellectually, physically, mentally, and socially then they will grow up to be the best versions of themselves. Having a holistic mentality and approach will encourage a child to have long-term success and happiness. Knowing that motivates me to show up for my children and others because I believe that everyone’s needs must be met to thrive in life, and focusing on all of those factors can make a huge and positive impact in people’s lives.

2. What inspires me to advocate for better child care and early education (CCEE) policies and experiences for children and families?

I’m inspired by the urgent need for change in systems that are outdated and no longer meet the evolving needs of today’s families. Families deserve options, flexibility, diversity, and inclusivity. Families need to be at the table when decisions are being made about them. I advocate for better CCEE policies because I’ve seen firsthand how the lack of access to child care and early education can shape a child’s future. I believe that when parents are part of the policy-making process, the outcomes are more equitable, inclusive, effective, and truly family-centered.

3. What is one of my biggest accomplishments as a parent advocate?

One of my proudest accomplishments has been successfully advocating for child care access for families who qualify but often fall through the cracks. I’ve also fought for my own child’s right to be evaluated when the health care system never saw anything wrong but I had a strong intuition that there was something wrong. Therefore, I followed up with health care providers and then went through a lengthy evaluation system to find out that my child did have a special needs diagnosis. So when he finally was given that diagnosis, I had to follow up with the school to make sure they were implementing the Individualized Education Program, ensuring that teachers, staff, and stakeholders stay engaged and accountable for his well-being and educational needs. When I lived in San Francisco I advocated for “Baby” Prop C, which is a commercial tax to fund early childhood education. The commercial rent tax applies to businesses with over $1 million in gross receipts. The passage of this proposition created funding for much-needed services. These personal and community wins have reinforced my belief that advocacy can lead to real, lasting change when passionate people are persistent, informed, organized, present, and involved in the process. We need to unite and work together to create the change we want to see in the world which will benefit those in need.

4. What excites me about this fellowship?

I’m excited to deepen my knowledge of child care and early education policy, understanding not only what needs to change, but how to strategically influence the decision-makers who can make it happen. I look forward to learning alongside other passionate advocates, understanding best practices for successful policies, gaining tools to elevate parent voices, and contributing to a movement that prioritizes investment in children. I truly believe it is better to support and uplift children early than to try and repair the consequences later in life. Therefore, we need to invite those impacted by the issues to get involved in the solutions, and we need to work with stakeholders and others to make sure we can successfully make a strong community impact.

5. How do I hope to use my skills and expertise to enhance the work of CLASP and the broader CCEE policy space?

I hope to contribute my passion, bilingual skills, educational background, and professional experience to amplify parent voices in policy spaces. I have professional work experience in the corporate world, education sector, and non-profit sector, demonstrating my adaptability and resilience in diverse environments. Most importantly, I’m committed to using my lived experience and advocacy to push for equitable, parent-informed solutions in early care and education. I hope to learn and collaborate with CLASP and the CCEE team to make sure we are creating diverse and inclusive policies in different states and on the federal and national levels. Families need options and different pathways to education and work which ultimately will be mutually beneficial for families and the economy by making sure kids are learning while parents are earning livable wages. Once people engage and help influence change, they will be empowered. Therefore, incorporating lived experiences while policies are created allows for a more effective, equitable, and relevant programs and systems. Individuals who have direct and firsthand knowledge on social issues that affect them can provide insights into policies to help change, improve, and create policies. Today more than ever it is important for everyone to get engaged and influence policy that has a huge effect on our lives.

6. Outside of my advocacy, what are some of my favorite things to do?

Outside of advocacy, I love spending time with my kids taking them to the park, encouraging play, and helping them build friendships and healthy habits through active fun. I encourage exploration and relationship-building with hopes they will socialize with others. I also look forward to giving my children new experiences and exposing them to different opportunities that I hope will help them grow. Traveling together is especially important to me; I want them to explore places beyond their comfort zone, see the diversity of the world, develop a broader appreciation for what they have, have a more compassionate perspective of life, and adapt to changes, which I hope will also persuade them to count their blessings. Hopefully they will find something they are passionate about while making this world a better place for all.

Read more about the fellowship here.

By Alecia Murray

1. What motivates me to show up as a parent leader and advocate?

1. What motivates me to show up as a parent leader and advocate?

My greatest motivation will always be my children. From my amazing adult daughter to my three active boys, watching them grow reminds me every day why parent voices matter. They’re the reason I stay involved, stay informed, and continue to advocate for families in my community. I really enjoy helping others, building relationships with parents, and sharing knowledge—from holistic health to policy advocacy, and community resources—because informed and empowered families strengthen entire communities.

Through my work with the Ohio Parent Advocacy Network (OPAN), United Parent Leaders Action Network (UPLAN), and other parent groups, I’ve seen just how powerful it is when parents have real seats at the table—and how often their voices are missing. That’s what drives me to stay active in different parent groups: to learn what’s happening across communities, share information, and help families feel connected and supported.

What keeps me going is that moment when a parent realizes their voice can spark real change. That energy inspires me to keep advocating every single day.

2. What inspires me to advocate for better child care and early education (CCEE)?

My inspiration to advocate for better child care and early education comes from my own journey as a mom. Before my three boys were enrolled in Head Start’s home-based program, I struggled to teach them with workbooks and flashcards. I wanted them to love learning, but it felt like something wasn’t clicking. Then a Head Start home-based teacher came into my home and began showing me how learning could be fun—through play, games, and everyday experiences. Watching my boys light up with curiosity during those moments changed everything for me. I realized that early education isn’t just about academics—it’s about connection, joy, and discovery.

During some of our family’s hardest times, the Head Start Parent Ambassador Program—the original name of OPAN—became a source of strength and community. Joining the Parent Ambassador program helped me heal and grow by connecting with other parents who shared their stories with honesty and courage. Hearing those voices made me realize how powerful it is when families are seen and heard. That’s what continues to inspire me: knowing that our lived experiences can shape policies and improve systems for every child and parent who comes after us.

What keeps me motivated are the small victories—the moments when a child grasps something new or when a parent realizes their voice has real influence. Those moments remind me why advocacy matters. When families are supported and their voices are truly valued, we don’t just improve early education—we build stronger, more compassionate communities for everyone.

3. What is one of my biggest accomplishments as a parent advocate?

One of my proudest accomplishments as a parent advocate has been co-founding the OPAN Alumni Group alongside a deeply committed group of parent leaders and my amazing mentor. After completing OPAN’s year-long training, many of us realized we weren’t ready to stop — the program had equipped us with so much knowledge, confidence, and momentum that parents wanted to stay involved, continue advocating, and keep building upon everything we had learned. That shared commitment is exactly why the alumni group was formed. As I continued growing through organizations like OPAN, UPLAN, the National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement (NAFSCE), and Groundwork Ohio, my dedication to empowering other parents only deepened. Helping build this alumni network with such a passionate group of parent leaders has shown me how powerful we can be when we unite with purpose—and how far our voices can carry across the state.

Another accomplishment I’m especially proud of is joining the Family Math Parent Advisory Council (PAC) in 2019. This council not only introduced me to UPLAN, but it also deepened my love for advocating in a space that feels so natural to me. Math has always been a joy in our home—something I love and something my boys genuinely enjoy—which makes advocating for high-quality family math opportunities for everyone to feel effortless. Through the PAC, I’ve connected with incredible parent leaders from across the country, and I’ve been inspired by the collective passion we share. With NAFSCE now leading the Family Math initiative, the work is thriving, and I’m excited to see how this movement continues to grow and support all families.

Seeing the OPAN Alumni Group and the Family Math PAC empower parents to share their stories, influence policy, and lead meaningful change has been incredibly rewarding. These accomplishments are more than milestones—they’re proof that when parents come together, their voices can transform entire communities.

4. What excites me about this fellowship?

This fellowship excites me because it gives me a platform to amplify parent voices on a national level and collaborate with others who are passionate about equity and family-centered policies. I’m always ready to learn from other parent leaders and experts, contribute my lived experiences, and help shape solutions that truly reflect what families need.

What excites me most about CLASP’s leadership in this fellowship is their strong commitment to teaching policy. I want to deepen my understanding of how policy works—how it’s created, implemented, and sustained—so I can use that knowledge to strengthen my advocacy. CLASP’s expertise in breaking down complex policy concepts and making them accessible to advocates like me will help me connect my lived experience to real policy solutions. Learning from CLASP’s approach will give me the tools to engage more confidently with decision-makers and translate community voices into informed, impactful action.

This fellowship is not just an opportunity to learn—it’s a chance to grow as a policy advocate, build relationships with others who share my passion, and turn our collective experiences into policies that truly support families.

5. How do I hope to use my skills and expertise to enhance the work of CLASP and the broader CCEE policy space?

I hope to bring my experiences as a parent and advocate to support CLASP’s work in shaping early childhood education and care policy. Having worked at local, state, and national levels with OPAN, UPLAN, NAFSCE, and Groundwork Ohio, I’ve seen firsthand the difference that parent voices make in creating meaningful, equitable change.

I want to use my skills to connect policymakers with the real stories of families—the challenges, successes, and ideas that come from lived experience. By sharing what parents need, helping families find their voice, and supporting collaborative initiatives, I aim to ensure that policies are not only informed by research but also grounded in the realities of everyday family life. My goal is to help parents feel empowered to influence the systems that shape their children’s education and well-being, so that every child has the opportunity to thrive.

6. Outside of advocacy, what are some of my favorite things to do?

My world really revolves around family and finding joy in everyday moments. I love spending time with my husband, our three energetic boys, and my adult daughter. Whether I’m cheering them on at sporting events, playing together at home, or exploring local parks, those moments fill me with joy and remind me why family is at the heart of everything I do.

I’m also really close to my parents and my big extended family. As the oldest of seven, I grew up surrounded by noise, laughter, and a lot of love — and that hasn’t changed. We still talk all the time, gather at my parents’ house, and lean on each other through everything. That closeness keeps me grounded and reminds me why strong family connections matter so much.

I am very passionate about holistic health and wellness (before the boys, I was an aerobics instructor). I love finding ways to take care of my mind and body—whether it’s practicing mindfulness; using singing bowls, tensor rings, or crystals; or experimenting with fermentation in the kitchen. These small moments keep me centered and give me the energy to tackle whatever life—or my kids—throws my way.

And then there’s my playful, slightly quirky side—I’m a total treasure hunter at heart. I love garage sales, thrift stores, and bargain hunting. (I used to be an extreme couponer, so finding a great deal still gives me a rush!) I get such a kick out of discovering hidden gems, repurposing things in creative ways, and sharing those finds with my kids. It’s fun, spontaneous, and always full of surprises.

I love embracing my playful, carefree side through the messy, hands-on adventures I share with my boys. We love to slip on a pair of mudding boots and slosh through creeks, wander through the woods foraging goodies, or simply explore the outdoors, observing wildlife and soaking in the beauty of nature. They’re the moments that make life joyful, messy, and perfectly imperfect—playful adventures that spark curiosity and become memories I’ll treasure forever.

All in all, my family, wellness practices, and love for simple adventures keep me balanced, inspired, and ready to bring that same energy and heart into my advocacy work.

Read more about the fellowship here.

About Us

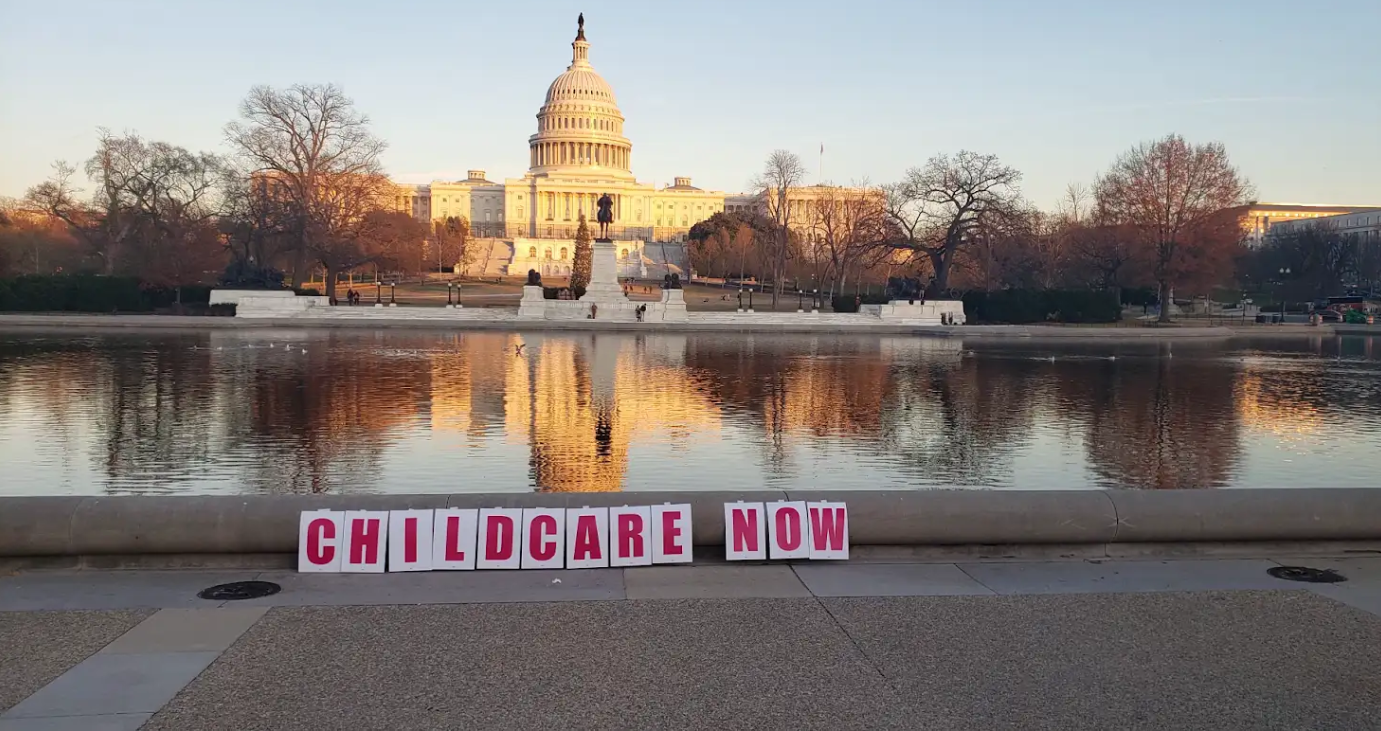

Centering and Elevating Parent Voice in National Child Care Policy

The CLASP Child Care and Early Education Policy Fellowship for Parents is designed to center and elevate the lived experiences of parents in the national child care policy space and integrate this expertise with the work of CLASP’s Child Care and Early Education team. This fellowship brings together parent advocates to inform, shape, and advance more equitable child care and early education policies by training fellows across CLASP’s issue areas and supporting their engagement with policymaking and advocacy at the state and federal level.

What the Fellowship Does

Through this fellowship, CLASP aims to:

- Build fellows’ knowledge of federal and state-level CCEE policy.

- Recognize and elevate parents’ lived expertise through active participation in advocacy and policy work.

- Provide professional development in lobbying, public speaking, writing, data analysis, and other areas.

- Foster deeper relationships between CLASP staff and parent leaders to strengthen future policy work.

And fellows will engage in:

- Networking opportunities with CLASP staff, mentors, and national policymakers.

- Contributing directly to federal and state advocacy efforts.

- Creating a personalized work portfolio and capstone project published by CLASP.

2025-2026 Fellowship Cohort

In September 2025, CLASP welcomed our first cohort of parent fellows. These two mothers are passionate, dedicated advocates fighting to ensure that all children have access to affordable, quality early childhood education:

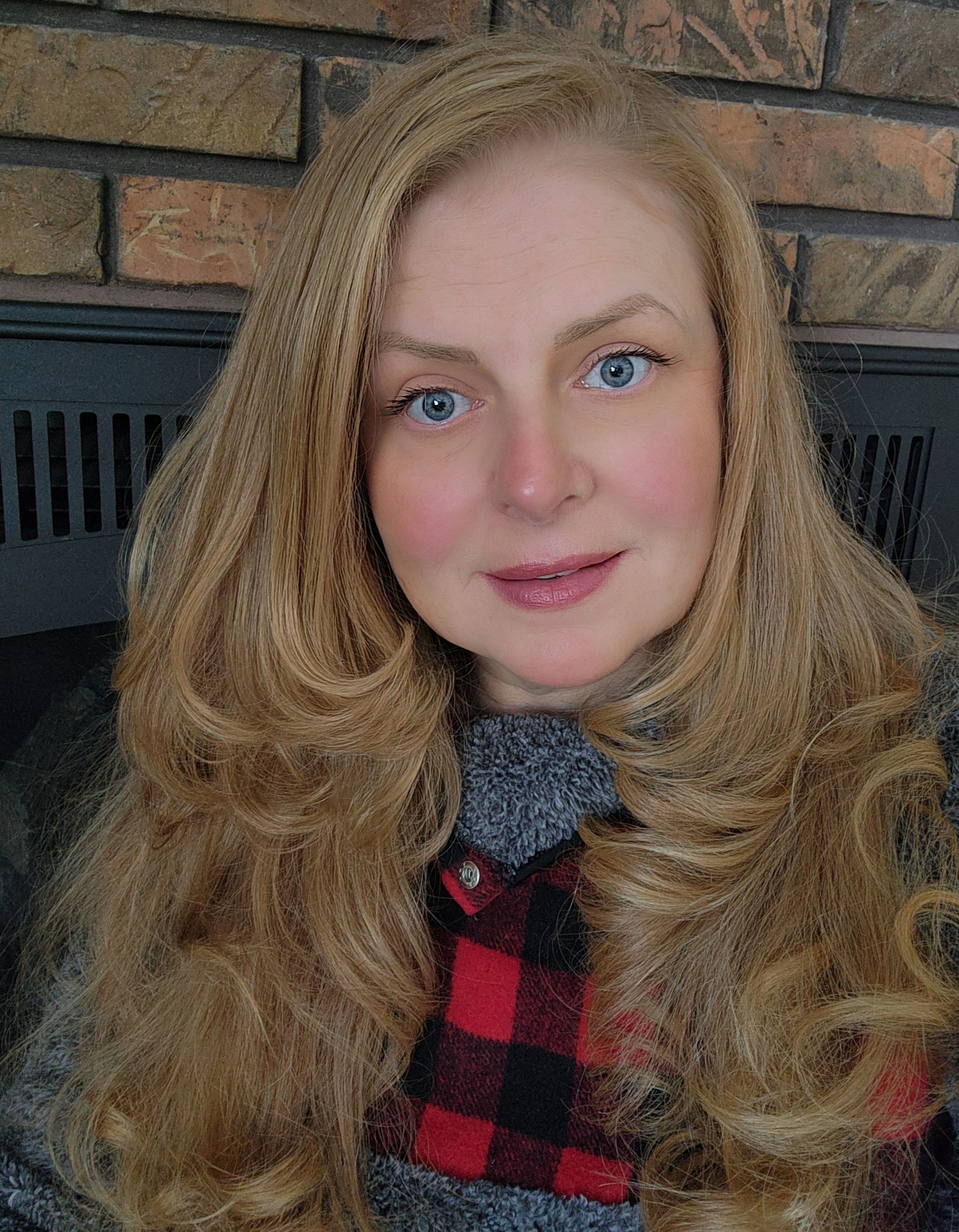

Alecia Murray

Alecia Murray

Alecia Murray is a parent advocate, wife, and proud mother of four — including her talented daughter, 30, and three energetic sons, ages 13, 11, and 9. Alecia’s advocacy journey began through her own experiences as a parent, which inspired her to speak up and ensure that families are truly seen, heard, and valued in the decisions that shape their lives.

Based in Lima, Ohio, Alecia has spent nearly a decade championing early childhood education, health equity, and parent leadership at both the state and national levels. She has served as president of her local Head Start Policy Council, board member of the Ohio Head Start Association Inc., and a fellow with Groundwork Ohio.

Alecia is also a co-founder of the Ohio Parent Advocacy Network Alumni Group, an initiative she helped launch alongside a group of parent leaders and her mentor to elevate parent voices and strengthen family leadership across the state. In addition, she serves as a committee co-chair with the United Parent Leaders Action Network, leading parents nationally in advocacy and systems change.

Nationally, Alecia contributes to the Family Math Parent Advisory Council with the National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement. Through this work, she helps create innovative strategies and resources that empower parents, teachers, and administrators to support children’s learning through everyday math experiences, connecting learning, play, and daily life while bridging families, schools, and communities.

Alecia holds a B.A. in Business Administration and an A.A.B. in Computer Information Systems, both earned with honors, and is a certified grant writer. Her mission—shaped by her experiences as both a parent and advocate—is to uplift families, inspire leadership, and build equitable systems where every parent’s voice makes a difference.

Alecia’s advocacy is rooted in the belief that parents are not just participants; they are powerful partners in building equitable, thriving communities. Whether she is speaking at national conferences, contributing to policy discussions, or mentoring other parents, Alecia strives to inspire others to stand up, speak out, and lead with purpose.

Learn more about Alecia here.

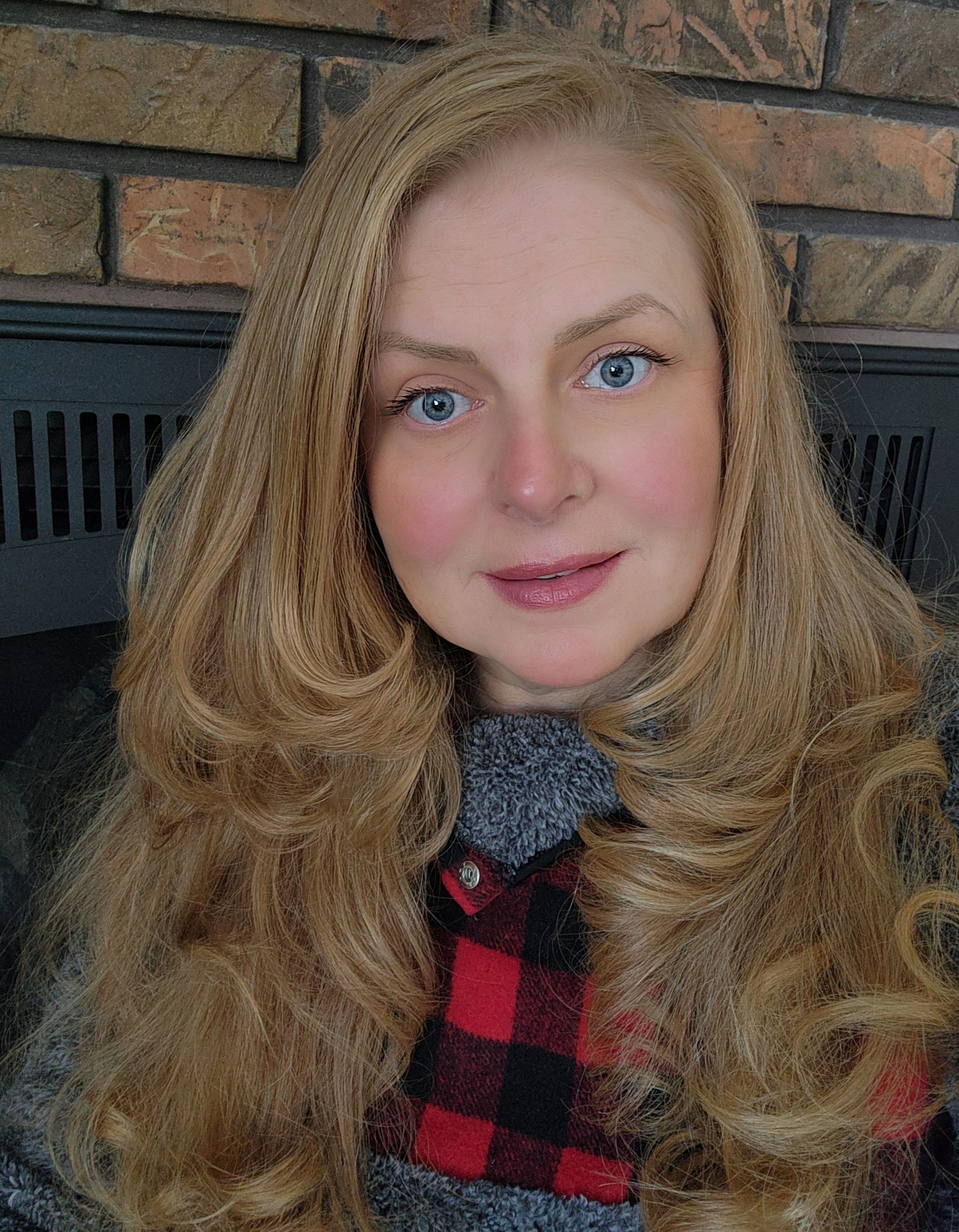

Lily Ana Marquez

Lily Ana Marquez

Lily Ana Marquez is an advocate for equity in education, child care, and economic justice. She was born and raised in Oakland, California. As a first-generation college student, she holds a B.A in sociology and communication from Holy Names University and an M.P.A in public management from California State University, East Bay.

With over 13 years of experience in higher education as a financial aid administrator and eight years as a parent leader with Parent Voices of California, Lily has been a steadfast champion for affordable, accessible child care and early education. Her advocacy journey began after she left the workforce due to the lack of child care for her two children, Mia (8) and Jeremiah (10). Her oldest child’s special needs and Individualized Education Program deepened her commitment to ensuring that all children, especially those with unique needs, receive equitable support and opportunities to thrive.

Guided by the values of humanity, equity, justice, and compassion, Lily believes policies should truly reflect the people they serve and emphasizes the importance of including those with lived experience in shaping solutions to the challenges that affect them. By centering the voices of impacted communities and key stakeholders, she strives to ensure that everyone has the resources, support, and opportunities they need to thrive.

Lily has been a parent leader with Parent Voices of California since 2018, and is also a parent leader with United Parent Leaders in Action Network at the federal level, representing parents and bringing her perspective as a parent and child care advocate in the early care and education space. She hopes to work with others across different states to make sure all families have equal access and that systems change to reflect the needs of the communities and are just, fair, diverse, and inclusive.

Lily currently serves as a program manager at a Bay Area nonprofit that works to dismantle poverty, where she uplifts community voices to shape programs, funding, and solutions grounded in lived experience.

Learn more about Lily here.

By Suzanne Wikle

The effect of H.R. 1 on the 10 non-expansion states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) did not receive the same attention as the bill’s primary Medicaid provisions. But Medicaid programs in these states will also be harmed by the bill. Eligibility and financing changes will force non-expansion states to make difficult decisions and likely lead to reduced services, lower provider reimbursement rates, and hospital closures.

On October 30, Rachel Wilensky and Mikayla Slaydon gave a presentation on how the current federal policy context of immigration impacts child care and early education, as part of the Spring Institutes Dual Language Learner Coalition Retreat.

By Wendy Cervantes and Jennifer Ibañez Whitlock

Updated November 2025

⇒Download in English ⇒Leer en español

Parents have a right to make decisions about the care and safety of their children, even while in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody. The National Immigration Law Center and Center for Law and Social Policy jointly developed this resource for immigrant parents which details the rights that parents have while being apprehended and detained. Under its own policies, ICE has a responsibility to ensure that detained parents have a say in the care of their children and keeping them safe.

Here are five things for parents to know about the policy:

- You have the right to make decisions about the care and custody of your child at the time of arrest.

- You have the right to be kept near your child and stay in touch with them while detained.

- You can ask for help in most detention centers to help you make plans for your children.

- You can be part of your child’s welfare court case while you are in ICE detention.

- You can decide whether your child will remain in the U.S. and make alternative care arrangements.

Help share this resource far and wide to make sure immigrant parents know their rights!

Legal Disclaimer: This resource provides general information. It is not legal advice specific to your situation. To find an immigration attorney, you can search for legal services by zip code by visiting the National Immigration Legal Services Directory.

November 18, 2025, Washington, D.C.– Yesterday, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released a proposal to repeal the 2022 public charge rule, which is applicable to immigrants applying for a green card, with plans to release more restrictive guidance at a later date. Without the 2022 rule in place, DHS officers would have wide discretion to make arbitrary decisions about granting a visa or green card based on a person’s current or former health and economic situation, as well as their past or potential use of a wide range of health and social service programs. By removing standardized guidance for DHS officers, the public charge determination process would be open to widespread confusion, discrimination, fear, and chaos. Once the rule is published, the public will have a 30-day comment period to provide input.

The proposed rule claims so-called cost ‘savings’ from people disenrolling from public benefits due to the chilling effect of these proposed changes. However, there is no mention of how public benefits contribute to public health and overall well-being and of the cost savings from providing preventive health care and access to nutritious food to people who cannot afford them. The proposal also aims to punish immigrants for using government support programs they pay into. Moreover, the Trump Administration even acknowledges that this rule would cause economic harm to our health care providers, grocery retailers, and farmers. Yet the administration is choosing to proceed with this rule anyway, prioritizing its crusade against immigrants over what’s actually best for the country and our economy.

CLASP is committed to ensuring that all families are able to meet their basic needs, and we will work alongside our partners to defeat this reckless public charge proposal as we did under the first Trump Administration.

In response to the proposed rule, Wendy Chun-Hoon, President and Executive Director of the Center for Law and Social Policy, released the following statement:

“This is yet another cruel attempt by the Trump Administration to sow fear and confusion among immigrant communities, deterring them from accessing critical services and supports, like seeking health care and food assistance essential to their well-being and that of their children. Providers who serve all communities will be forced yet again to struggle in navigating this ever-changing policy environment, wasting time and resources. As was the case when the first Trump Administration proposed public charge changes, this new rule will lead to millions of families missing doctor’s appointments, disenrolling from programs they are eligible for, and further isolating themselves. Children in immigrant families, including U.S. citizens, will once again face long-term developmental harms, which our country will ultimately pay the price for.”

This summer’s passage of H.R.1 threatens to drastically cut SNAP benefits, placing millions of families at risk of food insecurity. These policies directly impact families like Ashley Blair’s, for whom programs like WIC are not just helpful—they are lifelines.

This new blog series by Ashley, a member of CLASP’s Community Partnership Group and VOICE (Victory Over Injustice Creates Equality), examines the importance of food justice and access to essential programs like WIC, and reminds us that everyone deserves the resources they need to thrive.

By Ashley Blair

Questions I ask myself far too often when money is tight: “How do I feed my children today? Do we have enough to get groceries to last a few days? Lord, I need help.”

I’ve always had a passion for helping others, which led me to pursue both my B.S. and M.S. in Biology from The Tennessee State University. Our motto, Think. Work. Serve., is etched into my heart, and it has guided every step of my journey.

I am also a member of Sigma Alpha Iota International Music Fraternity (Kappa Iota chapter) and Alpha Phi Omega National Service Fraternity, Inc. (Psi Phi chapter) at The Tennessee State University. After college, I worked as a research analyst, research assistant, and clinical research coordinator at hospitals across Tennessee.

People often hear my credentials and wonder, “Why do you need public benefits with two degrees and a full-time career in health care?” The answer is simple: the math doesn’t add up. The average household income in Tennessee is around $56,000, and the income limit for WIC for a family of three is $49,303. I’m just one of the countless mothers who work full-time but still qualify for WIC.

Also known as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, WIC is a federally funded program that provides nutritious foods, nutrition counseling, and referrals to healthcare and social services for pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women, infants, and children up to age five who have low incomes and are at nutritional risk. WIC isn’t just a benefits program—it’s a lifeline that’s been linked to healthier births, lower infant mortality rates, improved nutrition, and long-term cognitive development for children.

I want to take a moment to express my deep gratitude for WIC, which supported me through one of the most challenging yet rewarding parts of motherhood: breastfeeding. On the day my daughter was born, I thought breastfeeding would come naturally—but it hurt, and I didn’t know what to do. Through WIC, I received not just guidance but hands-on, compassionate care. A medical professional came to my home to help me learn how to nurse my baby. That support changed everything.

When my second child was born at just 28 weeks, WIC once again made it possible for me to provide him with breast milk. That ensured I could give him the same nutrition and immune support that helped my daughter thrive.

Fully funding WIC ensures that all eligible families—including pregnant people of color and their infants, who face disproportionate health risks–can receive assistance. Last month, the White House announced a temporary funding patch using tariff revenues. While this shows some effort, it’s a short-term fix to a long-term crisis. Questions remain: How much funding will be provided? When will it be distributed? How long will it last?

If WIC is not fully funded, 6.7 million participants—including 41 percent of all infants in the United States–will be affected. This means mothers may lose access to healthy foods and breastfeeding support, directly affecting their children’s brain development and well-being. The resulting stress of not knowing how to feed your children is devastating, and that kind of stress has real physical and mental consequences: anxiety, depression, high blood pressure, and more.

I vividly remember taking my daughter to a dentist appointment where her exam wasn’t covered by insurance. I had to choose between paying for her dental visit or buying groceries. No parent should ever have to make that choice. Having access to WIC as a vegan family allows us to buy fresh fruits and vegetables, which has made a tremendous difference in our health and lives.

The National WIC Association (NWA) has made it clear: this temporary fix is not enough. A prolonged government shutdown—especially at the start of the fiscal year—puts millions of pregnant women, new mothers, and young children in jeopardy. Access to infant formula, breastfeeding support, and vital nutrition services must not be left to chance.

As NWA President and CEO Dr. Georgia Machell said:

“We welcome efforts to keep WIC afloat during the shutdown, but families need long-term stability, not short-term uncertainty… There is no substitute for Congress doing its job. WIC needs full-year funding, not just temporary lifelines.”

I couldn’t agree more. I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Machell at Bread for the World’s “Nourish Our Future” Campaign earlier this year in Washington, D.C. Her passion for food justice and equity inspires me daily.

Many families like mine rely on WIC for our most basic needs. The program cannot, and should not, be put on the back burner. Through the VOICE series and programs to come, we’re committed to keeping these injustices at the forefront—amplifying the voices of those most impacted and holding leaders accountable to act.

This is not a time for silence. It’s a time to lift every voice, demand equity, and ensure every family has access to the nutrition, care, and dignity they deserve.

Wendy Chun-Hoon spoke at the National Youth Employment Coalition’s 2025 Youth Days.

By Christian Collins

In this op-ed for Inside Higher Ed, Christian describes how student loan forgiveness is being used as a tool by the administration to recruit Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents. Among other things, he notes, “By passing the reconciliation bill that nearly tripled ICE’s budget while restricting Pell Grant eligibility for some students and cutting back basic needs programs like food stamps and Medicaid, congressional leaders have identified themselves as active participants in this strategy.”