A Black History Month Reflection on Key Leaders in the Fight for Civil Rights

By Barbara Semedo

4 min read.

Black History Month has long been an important moment to reflect on the often-ignored history and legacy of Black people. We owe a debt of gratitude to the scholar and educator, Dr. Carter G. Woodson, who set out more than a century ago to change that. He began his work in the early 1900s to document and tell the story of the history of Black people through his scholarship and study of the contributions of African Americans whom he once described as being “overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them.” His signature publication, originally called The Journal of Negro History, continues to exist as the Journal of African American History, an invaluable resource for the study of Black history, then and now.

Dr. Woodson’s legacy of commitment to recognize the history of African Americans led to his creation and introduction of Negro History Week in 1926. He intentionally selected the second week of February as a tribute to Abraham Lincoln’s birthday and to the birth month of Frederick Douglass, the great abolitionist, orator, writer, and activist who was born into slavery. Douglass never knew the exact date of his birth in 1818, but his life and legacy, like Dr. Woodson’s, was also defined by what is the continuing work of policy advocates for recognition, equity, healing, and meaningful social and economic justice for Black Americans. In 1970, the week-long observation was expanded to become Black History Month.

Dr. John Hope Franklin carried forward the work of Dr. Woodson and Frederick Douglass with his 1947 book, From Slavery to Freedom, A History of African Americans, now in its 10th edition.

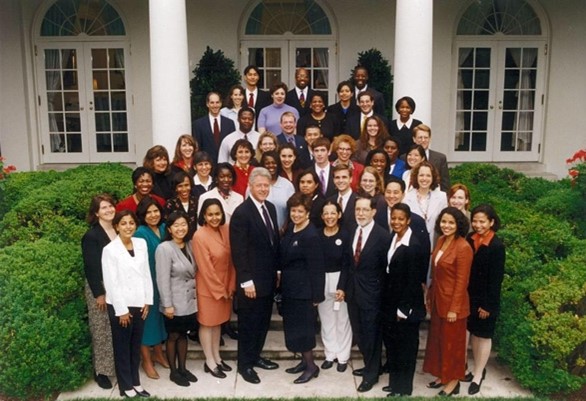

I had the rare opportunity to work with Dr. Franklin when he co-chaired President’s Clinton Initiative on Race in 1997. His brilliant career as an educator and historian is long and illustrious, like those of Frederick Douglass and Dr. Woodson.

I was honored as the communications director for the Initiative on Race to get to know Dr. Franklin, someone who would leave us all with a legacy of telling the unvarnished story of slavery and racism. I had the privilege of sitting across from him in meetings and ghostwriting an op-ed, “Talking, Not Shouting about Race,” for the New York Times. He shared with many of us on the staff one of his personal experiences with racism, even as he was about to receive national recognition for his work.

The story he shared related to an experience in 1995 when he was presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Clinton at a White House ceremony. The night before, he invited some friends to meet him for dinner at the Cosmos Club, a private social club in D.C.

Dr. Franklin was the first African American elected in 1962 to membership in the Cosmos Club. As he waited in the lobby to greet his guests, a white woman walked up assuming this Black man standing there must be one of the club’s workers. So, she handed him her coat check ticket and demanded he get her coat – to which Dr. Franklin politely declined and suggested she talk to one of the other “uniformed staff” for assistance. Dr. Franklin shared that story as a sharp and vivid reminder that no matter the social position we as Black people achieve, racism, stereotyping, and social inequity are still entrenched in American society.

Of course, our nation has many moments in the long, historic fight for racial, social, and economic justice that originated with figures like Dr. Carter G. Woodson, Frederick Douglass, and Dr. John Hope Franklin. On June 10, 1964, after contentious debates in Congress, the U.S. Senate passed the landmark Civil Rights Acts of 1964. President Johnson signed the bill into law on July 2, 1964, surrounded by the preeminent civil rights leaders who suffered the same unspeakable indignities, harm, and racism as those who came before them.

In looking back over the 60 years since the passage of the Civil Rights Act, there are many memories and positive stories to reflect on as we approach the closing days of Black History Month. But the work started by many of those we honor this month is far from over.

I want to share these words from President Johnson’s address to a joint session of Congress in November 1963 when he made the case for the Civil Rights Act shortly after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, “We have talked long enough in this country about equal rights. We have talked for one hundred years or more. It is time to write the next chapter, and to write it in the books of law.”